Picturebooks - Good and bad

Andy McCormack

Monday, August 5, 2019

The good, the bad and the ugly: what picturebooks teach children about beauty and self-worth. By Andy McCormack

Download the PDF of this article

In her cultural history of ugliness, Gretchen Henderson describes how, in fairy tales, ugliness is often ‘counterpointed with beauty, to delineate good from evil’. Thankfully, the children we teach are growing up in a post-Shrek world – in which the equation between good and bad and beautiful and ugly isn’t as clear-cut as once it might have been. However, we still have a long way to go in challenging the prevalence of this idea in children’s culture.

So many of our fairytales still adhere to only one vision of beauty: drawings of Cinderella I observed, in picturebooks and in children’s artwork, when I was teaching in nursery and Reception, were still overwhelmingly thin, white and blonde.

Last year, the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education’s study looking at diversity in UK children’s literature found that only 4 per cent of the 9,115 children’s books published in 2017 featured non-white characters at all, let alone in a way that celebrated beauty and goodness beyond the traditional model. It is unsurprising then that so many of the girls I taught came to school on World Book Days and party days with Princess Elsa from Frozen’s long blonde ponytail clipped over their own natural hair.

BREAKING THE BINARY

As early years teachers and practitioners, we have a responsibility to challenge harmful stereotypes and negative associations and, indeed, the lack of positive representation of diversity and difference, at their very root. Our settings should be environments in which difference is celebrated and everyone is valued equally.

Fostering a robust sense of self-worth is a core part of the EYFS for a reason: good personal, social and emotional development in the early years is a core foundation stone in a happy and healthy life.

Worryingly, a 2017 British Medical Journalreport detailed a 68 per cent increase in self-harm among girls aged 13 to 16. Then a survey carried out by the Children’s Society just last year of 11,000 14-year-olds found that a quarter of girls and one in ten boys had self-harmed.

Undoubtedly, the increased scrutiny and pressure young people today feel about their appearance has been heightened by social media. With children gaining access to online accounts at so young an age, it is vital to begin the work of breaking the binary that Henderson identified between traditional ‘beauty’ and feelings of self-worth. If this unhelpful binary is rooted in the very first stories we tell children, surely then these stories can also provide one of the best channels through which we can challenge it.

CHALLENGING THE LINKS

There are still many picturebooks that repeat the tired fairytale trope of traditional Western beauty standards signalling goodness, and non-traditional appearance or explicit ‘ugliness’ signalling badness. However, there are far more being published today, I think, which challenge these associations in exciting, amusing and intelligent ways.

Some of the first picturebooks to deconstruct fairytale stereotypes humourously come, perhaps unsurprisingly, from the 1980s – and still retain their ability to challenge and surprise child audience’s expectations.

It is heartening to see books like Babette Cole’s Prince Cinders and Robert Munsch and Michael Martchenko’s The Paper Bag Princess approaching well-earned and much-beloved ‘classic picturebook’ status.

It is heartening to see books like Babette Cole’s Prince Cinders and Robert Munsch and Michael Martchenko’s The Paper Bag Princess approaching well-earned and much-beloved ‘classic picturebook’ status.

Both books take fairytale tropes and turn them on their heads. Prince Cinders doesn’t need to change how he looks, and the paper bag princess doesn’t care about being beautiful or traditionally princess-like (passive and in need of a prince to come and save her): her feistiness and independence are far more interesting and appealing than the colour, length or softness of her hair.

Anna Kemp and Sara Ogilvie’s The Worst Princess, published in this decade, owes a clear debt to The Paper Bag Princess and is another excellent picturebook that empowers readers and celebrates independence over trying to fit in to restrictive, traditional models of beauty.

MODELS OF BEAUTY

Books which offer other models of beauty to the traditional princess template can also be helpful in starting conversations and dealing with issues of difference and multiculturalism in the classroom. I used a copy of I Love My Hair! by Natasha Tarpley as a central storytime book at a time when my own Reception class students were beginning to notice one another’s different types and styles of hair, and it proved a really helpful resource in steering conversations in a more celebratory and respectful direction.

Books which offer other models of beauty to the traditional princess template can also be helpful in starting conversations and dealing with issues of difference and multiculturalism in the classroom. I used a copy of I Love My Hair! by Natasha Tarpley as a central storytime book at a time when my own Reception class students were beginning to notice one another’s different types and styles of hair, and it proved a really helpful resource in steering conversations in a more celebratory and respectful direction.

One of the great joys of picturebooks is that while some, like I Love My Hair, can speak directly and explicitly to real-life issues and experiences our young pupils are just starting to negotiate, others can use the fantastical language and imagery of fairytales and the imagination to do the same work in equally powerful ways.

Something Else by Kathryn Cave and Chris Riddellis a perfect example of a picturebook which uses magical creatures to explore issues of teasing and exclusion because of appearance. Its clever twist at the end, and the introduction of a human child, makes explicit the connection between the experience of storybook characters and that of ourselves and our friends in the classroom.

Something Else by Kathryn Cave and Chris Riddellis a perfect example of a picturebook which uses magical creatures to explore issues of teasing and exclusion because of appearance. Its clever twist at the end, and the introduction of a human child, makes explicit the connection between the experience of storybook characters and that of ourselves and our friends in the classroom.

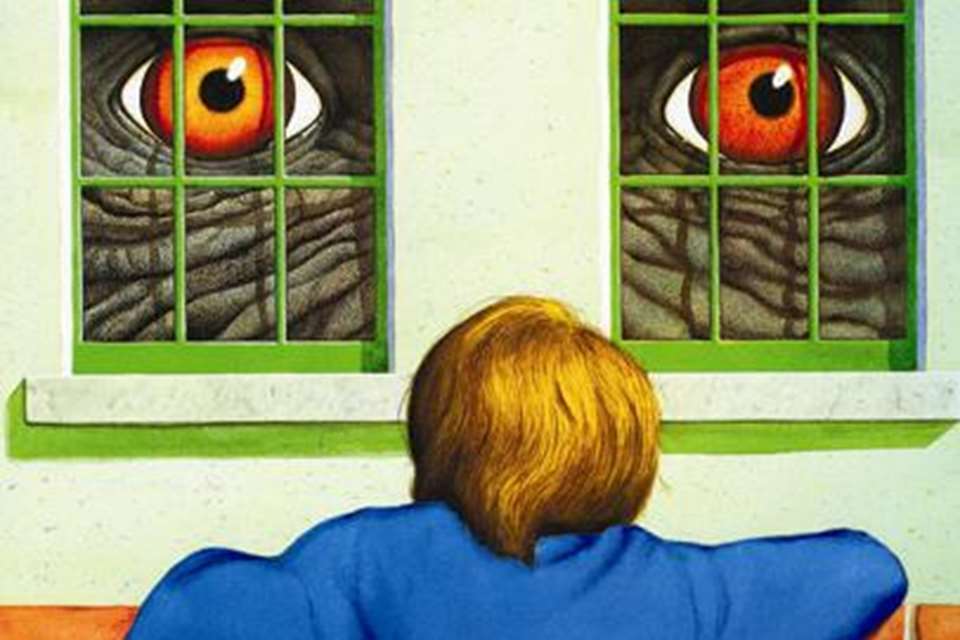

Another of the great, irreverent joys of the picturebook is its ability to celebrate difference through illustration. Many of the most beloved picturebook characters are made interesting not by their beauty but by their ugliness or difference: think of the Wild Things, the Gruffalo, and the joyfully eccentric Winnie the Witch.

Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler’s The Ugly Five doesn’t shy away from the word or concept of ‘ugliness’, but by cleverly shifting the focus onto families from the animal world it provides another space to question the binary between inner and outer beauty tied up in less-enriching stories for children.

Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler’s The Ugly Five doesn’t shy away from the word or concept of ‘ugliness’, but by cleverly shifting the focus onto families from the animal world it provides another space to question the binary between inner and outer beauty tied up in less-enriching stories for children.

TRADITIONAL PROBLEMS

It is retellings of traditional fairytales, rather than the innovations of Donaldson and Scheffler, that can perhaps provide some of the trickiest ground for avoiding a simple endorsement of their often problematic equation between beauty and goodness. Even Hans Christian Andersen’s The Ugly Duckling is less progressive than it seems, in that the little duckling only achieves a sense of self-worth when he becomes ‘beautiful’ as an adult.

Stephanie Campisi and Shahar Kober’s The Ugly Dumpling updates Andersen’s obviously good intentions in writing a truly empowering, modern alternative. The little dumpling, unlike his duckling ancestor, shows us that we don’t need to become beautiful to live happily ever after: all of us, in our own ways, already are.

Finding picturebooks which break the fairytale binary between beauty and self-worth is an important way to move the stories we tell children forward, and to equip them with narratives that celebrate difference and individuality over a traditional, one-size-fits-all understanding of what goodness and beauty really are.

SPELLS by Emily Gravett

One of the most interesting and engaging picturebooks to break the fairytale binary between beauty and goodness is Spells by Emily Gravett.

One of the most interesting and engaging picturebooks to break the fairytale binary between beauty and goodness is Spells by Emily Gravett.

The little frog in this interactive picturebook finds a book of spells to turn himself into a handsome prince. Gravett (or ‘Gribbett’, as she represents her own name within this froggy book) uses the possibilities of the picturebook to allow children to help frog in casting his magic spells: the split pages at the centre of the book let child readers turn frog into a half prince, half bird, a half newt, half rabbit, and all sorts of amusing combinations. The true twist, however, teaches a doubly important lesson.

Once he becomes a handsome prince, our hero is transformed back into a frog when kissed by a beautiful princess. He comes to discover she might not be as beautiful as he thought as she abandons him in his true form. He learns the lesson, too, of the importance of literacy: the warning about his transformations was in the small print of the book all along!

10 books to get started

Spells by Emily Gravett(Macmillan Children’s Books)

Spells by Emily Gravett(Macmillan Children’s Books)

Slug Needs a Hug by Jeanne Willis and Tony Ross (Andersen Press)

I Love My Hair by Natasha Tarpley (Little, Brown Books)

The Ugly Dumpling by Stephanie Campisi and Shahar Kober (Mighty Media Kids)

Perfectly Norman by Tom Percival (Bloomsbury)

Perfectly Norman by Tom Percival (Bloomsbury)

Prince Cinders by Babette Cole (Hamish Hamilton)

The Ugly Five by Julia Donaldson and Axel Scheffler (Alison Green Books)

Something Else by Kathryn Cave and Chris Riddell (Viking Children’s Books)

The Three Little Wolves and the Big Bad Pig by Eugene Trivizas and Helen Oxenbury (Heinemann)

The Three Little Wolves and the Big Bad Pig by Eugene Trivizas and Helen Oxenbury (Heinemann)

The Paper Bag Princess by Robert Munsch and Michael Martchenko (Annick Press)

MORE INFORMATION

MORE INFORMATION

www.juliadonaldson.co.uk/index.php

Andy McCormack is an early years teacher who worked in North London. He is currently studying for his PhD at the Centre for Research in Children’s Literature at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge.