All about...literacy

Julian Grenier

Thursday, April 4, 2002

Our special guide navigates the literacy debate and offers appropriate strategies for supporting literacy in the Foundation Stage. By Julian Grenier, acting head of Woodlands Park Nursery Centre, part of the London Borough of Haringey's Early Excellence Network

Download the pdf

[asset_library_tag 1667,All about literacy]

CONTENTS

- A GOOD READ – The literacy debate in the early years

- HOME BASE – Starting points for assessing and developing children's literacy

- TO THE LETTER – Understanding and supporting children's literacy across the Foundation Stage

A GOOD READ

As the debate over formal education in the early years rages on, you will need to make a professional judgement about the appropriate curriculum for children in your setting

There is a battle going on, and the youngest children in the educational system are right in the middle of it. To put the conflict most bluntly: is the National Literacy Strategy raising standards or damaging young children?

A fundamental part of the controversy is the concern that the educational system in England is expecting too much, too soon of its youngest children. In many European countries, children do not start formal education until they are six or seven years old. Yet in England there have been examples of children entering reception classes aged just four and being expected to manage a whole literacy hour.

When the National Curriculum was introduced in 1989, lower-achieving seven-year-olds were expected to 'begin to recognise individual words or letters in familiar contexts' at the end of Key Stage 1. Currently, the early learning goal for children at the end of their reception year is that they should 'read a range of familiar and common words and simple sentences independently'. In other words, children are expected to achieve much more than they were 13 years ago, but with two years less schooling. This is a massive change in official expectations. Yet evidence from European studies suggests that although children in England start formal schooling earlier than their counterparts, their achievements in reading at age 11 and 14 are lower.

High expectations

With the very high expectations of the early learning goals in communication, language and literacy come immense pressures on early years practitioners from headteachers and from parents. Often, these focus on the need for children to reach certain levels of skill by the time they start school. So it has become increasingly common to see children in nurseries working on handwriting worksheets and other formal activities. Anecdotal evidence suggests that some children are already disaffected with school by the time they reach reception, and that difficult behaviour and exclusions are on the rise because of these excessive demands.

Important though these debates are, they risk being unproductive to early years practitioners. It is not easy to make decisions and to act if you are caught in the crossfire. This supplement aims to look critically at what research is saying about how young children learn. It is hoped that, in turn, this helps practitioners begin the process of making professional judgements about the appropriate curriculum for the children they work with - judgements which are supported by evidence, judgements which will stand up to the questioning of parents, headteachers and Ofsted inspectors.

Legal status

The framework for the education of children from age three to the end of the reception year is the Curriculum Guidance for the Foundation Stage, which is due to have legal status like the National Curriculum from September 2002. In addition, the National Literacy Strategy provides guidance for teaching and learning in reception classes. It is not legally binding. Both the National Literacy Strategy and Ofsted's framework for the Inspection of schools recommend that aspects of the literacy strategy are taught in reception, but that a whole literacy hour should not be introduced until the end of the summer term.

The implication for practitioners is that their key planning document is the Curriculum guidance for the foundation stage, which emphasises the importance of play, first-hand experiences, and learning in real and meaningful contexts.

Later start

It is not clear that a later start to school would boost children's achievements in reading and writing. There are many more children living in poverty and disadvantage in England than there are in European countries with a later start to school, like Finland, Sweden and Denmark. This is a huge problem that needs attention for its own sake. So the figures for children's achievement in reading and writing need to be adjusted to take account of the impact that poverty can have on children's capacity to learn. Once this adjustment is made, the evidence does not show a link between starting school later and higher levels of achievement in reading at 11 or 14.

There are many good reasons for advocating a later start to formal schooling in England. For example, young children often experience restrictions in space, choice and independence when they transfer to reception. But in terms of the impact on children's achievements in reading and writing, the key question is: what sort of curriculum do children encounter when they start school?

Two extremes

Opinions about the curriculum have tended to take up one of the two extreme positions: either practitioners judge that children should be allowed to get on with playing freely or they judge that the children must be taught literacy formally.

Tricia David's recent study of nurseries and pre-schools in England shows how these two views can even live side by side. In several settings she observed play being interrupted so that children could be led over to a table to do their worksheets. On completion, they would be sent back to their play. The settings advocated play as a medium for learning. But they acted as if learning about literacy would only happen through direct teaching and the completion of worksheets.

Some practitioners are reluctant to plan for learning about literacy because they are concerned that the children are not yet ready. But evidence does not support the idea that children have to pass through pre-determined stages of development before they are ready to learn about reading and writing. Other practitioners hope that through providing good resources, they will help children to 'catch' knowledge about reading and writing. But literacy is not like a cough.

Recently, some more complex but also more exciting theories and practices have taken hold. Children's early learning about literacy is being seen as part of the wider attempt to grapple with the world and to make sense of it. Children are active seekers after meaning. They need adult guidance, help and direct teaching if they are to succeed in making sense out of their worlds. But they are also powerful learners, observers and experimenters in their own right.

Effective planning

The difficulty for practitioners is that this view of children's learning can seem to have little practical application to their work. For example, being told that children are active constructors of meaning does not give you a clear idea about how - or whether - to teach children the names, sounds and shapes of letters. Sometimes researchers and writers about early literacy seem to avoid these practical questions. That leaves the road wide open for the published booklets of photocopiable worksheets.

However, it certainly is possible to develop practical and effective planning from a starting point that children are active learners who are seeking after meanings. To do this, we have to get to know each child we work with. We need to know about how children learn, and what we will need to teach them. And we need to ensure that children move as smoothly as possible from home to their first educational setting, and from that setting on to reception.

Children should not be experiencing bewildering changes when they move from one phase of the Foundation Stage to the next. After all, we wouldn't accept that for older children in the run-up to their GCSEs. This supplement aims to consider how practitioners can plan coherently for children's early learning about literacy across the three years of the Foundation Stage.

Further reading and browsing

- David T and others Making sense of early literacy (Trentham Books)

- Dombey H and others Whole to part phonics: how children learn to read and spell (available from the Centre for Language in Primary Education. Tel: 020 7401 3382)

- Medwell J and others Effective teachers of literacy http://www.leeds.ac.uk

- Nutbrown C Recognising early literacy development (Paul Chapman Publishing)

- Nutbrown C and Hannon P Preparing for early literacy education with parents: a professional development manual (NES Arnold/REAL Project)

- Reading Reform Foundation www.rrf.org.uk

- Sharp C Age of starting school and the early years curriculum: a select annotated bibliography http://195.194.2.100/research/papers/Agmearly.doc

- Whalley M and others Involving Parents in their children's learning (Paul Chapman Publishing)

- Whitehead M Language and Literacy in the Early Years (Paul Chapman Publishing)

- Pinker S The Language Instinct (Penguin Books)

HOME BASE

Practitioners need to work in partnership with families to develop a child's understanding of reading and writing

Children first learn about literacy at home. And families vary greatly in the ways that they introduce ideas about reading and writing to children. To take a few examples, some families may not talk much about literacy, but children will observe writing, print and labels at home and in their neighbourhood. Children may become familiar with 'environmental print' in logos like McDonald's or Bob the Builder, road signs and shop signs, or video labels. Children may see adults writing notes, handing over receipts at a shop till or sending text messages on their mobile phones.

Other families talk more about the reading and writing that they do. Parents may point out letters and talk about how family names are written. They may show children what they are writing. They may encourage early writing, like pretend shopping lists and 'signing' birthday cards. Stories and books might be frequently shared. In still other families, there is not so much of this informal talk and participation. The children are taught aspects of literacy directly by their parents - maybe the names of the letters of the alphabet, or how to write their names. In many families, children grow up knowing about literacy in two or more languages.

It is also important to remember that some parents find reading and writing both difficult and stressful. There are increasing numbers of courses in adult literacy being organised for parents. There are also family literacy courses for parents and children together. When these courses are taught with sensitivity to the needs of adult learners, they can have a very positive impact.

Early experiences

The implications of children's different early experiences are important. No child starts the Foundation Stage knowing nothing about communication language and literacy. It is up to the practitioner to find out what the child knows and then to work in partnership with the child's family to build upon this.

Partnership does not simply mean that practitioners inform families of what they are doing to promote each child's learning. It means that there is a two-way flow of information. Planning for the child, and assessment of her or his progress, takes full account of what the child is doing at home. Practitioners can then blend their professional understanding of how children learn with the unique insights that parents have into their own children.

For children learning English as an additional language, it is important for practitioners to emphasise the importance of the first language. Once again, the first step is to find out about children's experiences of literacy at home. Such experiences might include encountering print in their first language, either at home or in shops and places of worship. There may be a tradition in their culture of storytelling or acting out stories through dance.

Practitioners need to build upon what they find out from families in a real, not a tokenistic, way. For example, practitioners could invite parents into the setting to read stories to children in their home languages, or organise a cooking session involving a parent speaking in the family's first language. There could be examples in that language of print on food packets and in the recipe. Books and labels in the setting could be multilingual.

The important principle here is that each language has status in its own right. There is little value in having a bilingual book if the adults only read the English and ignore the other script. Children's mark-making and early writing will look different according to their experiences of writing at home. For example, it would be important for a practitioner to value the right-to-left mark-making of a child who sees adults writing in Arabic at home.

Starting points

The important thing to remember is that children begin with different starting points. In their families, there are different understandings of what literacy means. We should not expect that children will make progress one step at a time through a series of developmental stages. Their progress is less predictable than that. Practitioners need to:

- Identify and support what children do well. A child who knows a lot about environmental print needs to have this recognised, valued and encouraged. There should be opportunities for the child to interact with this type of print. Such opportunities could take place in the setting, or on a trip or a walk to the shops. The practitioner can build on this interest and expertise by talking to the child about individual letters in the logos and print.

- Widen children's experiences from their initial starting points. A child who knows a lot about logos could be introduced to storybooks which are full of labels and signs - for example, The Great Pet Sale by Mick Inkpen (Hodder Children's Books, £5.99).

The practitioner role

Practitioners need to help each child to learn. They must recognise the child's current understanding and achievements and know what the child's next steps could be. This may involve the practitioner and the child working together in an activity chosen by the child. The practitioner can help children to achieve something new, that they could not yet do independently. It may involve the practitioner in talking with the child to establish what he or she understands.

The practitioner also needs to know what misconceptions the child holds about, for example, how letters represent the sounds in speech. Such information will provide the evidence for the practitioner's judgement about what the child needs to be taught and helped with. In these processes, both the child and the practitioner play an active role together.

Ready or not

On the other hand, when the children are all expected to do the level one worksheet in the writing scheme in the same week, they are just passive recipients. There is no planning here for the children's different types of understanding about writing, or for their different levels of fine motor control.

Likewise, practitioners are taking a passive role if they are simply waiting for signs that a child is 'ready', according to an assessment checklist, to start to learn about reading or writing.

With the 'readiness' approach, the most capable children in the eyes of the practitioner receive more interaction and teaching, whereas the less capable children are left with less support and planning. Once these kinds of gaps open up, they can widen rapidly. The children who experience early success get positive feedback and then more teaching. They achieve more success. The children who experience failure start to feel that they are incapable of learning about reading and writing. They will soon become disaffected.

Hard evidence

Practitioners need good and manageable systems for recording children's achievements. At the heart of this is collecting evidence of what children are actually doing. This means writing regular observations and analysing them to determine the next steps of planning and teaching. It means talking regularly with parents and carers and coming to a shared viewpoint about each child's interests, needs and achievements.

This process of assessment needs to be mapped on a framework of children's learning and development, if it is going to help the child to make progress. Otherwise practitioners may be building up a lot of information about children, but finding it difficult to turn it into effective planning. The Sheffield Early Literacy Development Profile (included in Cathy Nutbrown's Recognising Early Literacy Development, Paul Chapman Publishing, 15.99) requires more practitioner time than most settings could manage. But it can be used as a starting point to developing your own 'map' of indicators that children are learning about literacy.

Outcomes

Practitioners in the Foundation Stage often experience huge pressures for future outcomes. Planning activities for three-year-olds from the starting point of an early learning goal which is for five- to six-year-olds is hardly likely to result in effective teaching. Practitioners must take a clear stand based on evidence about children's learning, and produce evidence of children's progress from their own settings.

Further information

For information about organising adult literacy and family literacy courses, contact the Basic Skills Agency at www.basic-skills.co.ukor tel: 020 7405 4017.

TO THE LETTER

Environmental print and shared writing are just some of the ways to support children as they develop an awareness of the written word

Practitioners need to understand children's growing awareness of the written word and know how to support and develop that understanding. For children within the Foundation Stage, that awareness can be divided into three main 'windows'. Below is an outline of each and suggestions on how to support and extend children's learning and development in each phase.

Window 1: a growing awareness of print

Children will be aware of the meaning of some print, for example:

- logos like McDonald's, Coca-Cola or Bob the Builder

- their own names in a familiar context, like on a placemat or coat peg

- their own mark-making, which may look like letters or writing, even though there may be no real letters at all.

Support

- Look for familiar logos in the neighbourhood or display logos in the setting. Ask families to supply one piece of print that their child can read (languages other than English could be encouraged). Build up the contributions into a display of print that different children can read and talk about. Draw children's attention to the finer detail of the logos rather than just the overall look. Can children spot the first letter of their names in any of the environmental print? Can they spot any recurring letters? For example, young children can often spot the recurring 'T' in 'Tweenies', 'Teletubbies' and 'Thomas the Tank Engine'.

- Support children with special needs or disabilities by using alternative ways of communicating. Such methods may include Braille, objects of reference (collections of real objects to point to or look at), symbols or pictures. All children in the setting should have experiences of using such systems, and sometimes this will involve direct teaching.

In small story groups and throughout the session, encourage children to use symbols, pictures or objects of reference to communicate with each other. In small story groups, the opportunity to handle a puppet or real object connected with the story will support all children, specifically those with special needs. For example, when reading We're going on a bear hunt by Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury (Walker Books, £1.99), have a set of trays at the ready with mud, water, twigs, grass and a soft toy bear in them. The children could touch and handle these objects as you read the story. For more ambitious multi-sensory learning, the children could take off their shoes and socks and experience putting their feet into the trays and end up snuggled up together under a big duvet.

- Create a print-rich environment with the children. Labels and notes written when the children are around, with their input and ideas, are likely to be meaningful and memorable. You could start this with a comment like, 'It looks like we need somewhere to keep Lego models safe. How can we make sure that no one will break up the models if we put them on that shelf?' In this way children are creating meanings with adults. They are learning that writing is about communicating a message that matters. The print in the room will look messier, but it will be richer in meanings for the children.

Children's play experiences can always be resourced to support learning about early literacy. Home corners can have telephone books, recipe books, notepads, catalogues and magazines and newspapers in more than one language. Other role-play areas can similarly be resourced with print and opportunities to write.

Outdoor areas can have clipboards and notepads for writing on the move, street signs, number plates for the bikes and opportunities to make huge marks with big paintbrushes and rollers.

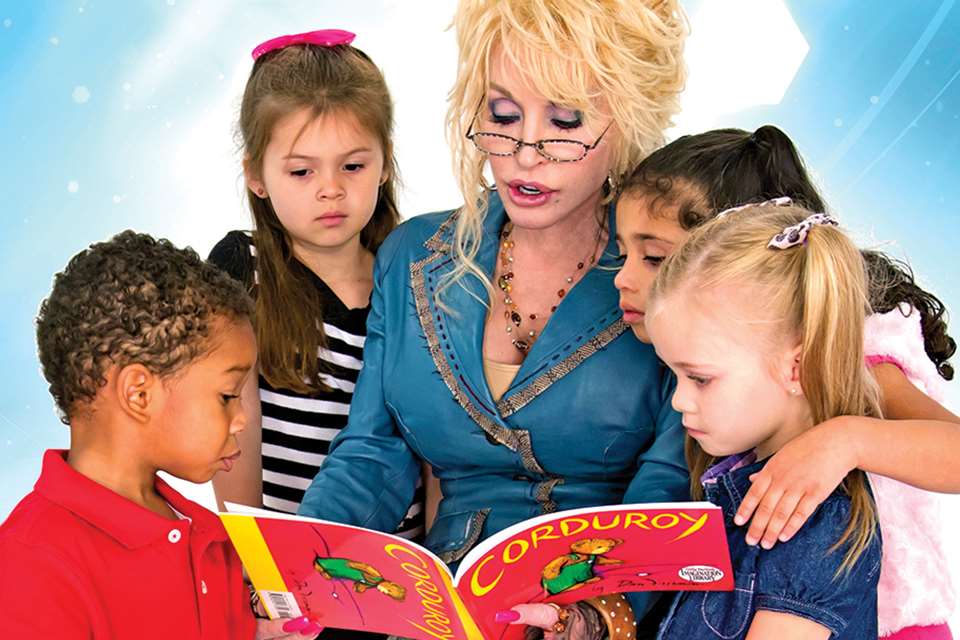

- Think carefully about ways of reading to young children. In large story groups, children are essentially passive recipients of a performance. The main thing they may learn from this is a set of social conventions. They are expected to sit and listen. They are not expected to enter into much discussion about the book, unless directly asked a question. So there may not be much literacy learning occurring. In a small group of five or six, each child can make a contribution about the story. Encourage each child to find their own meaning through having space to comment. Children who do not offer any comments can be sensitively but directly asked for a response by the practitioner, although it remains their prerogative whether they reply or not.

It is also worth thinking about what kind of questioning is useful. When reading We're going on a bear hunt, asking questions like 'What colour is the bear?' or 'How many children can you count?' will make no contribution to children's literacy learning. However, wondering aloud why the family raced away from the bear and encouraging the children to talk about occasions when they were frightened draws the children directly into the meaning of the text. This immersion in meaning is an essential part of becoming a reader. If children are read to in smaller groups, they will experience story groups less frequently, but each occasion will be richer in learning.

- Link with other ways of making meanings. A story could lead to the children planning a dance, with the adult selecting a range of music for the children to choose from and making space for rehearsal and possible performance. Children can also participate in stories by having puppets and other story props to handle. Access to the props throughout the day will allow them to replay the story and to improvise different narratives with the characters and objects.

Window 2: a growing awareness of detail

Children show that they are beginning to spot patterns or notice some precise features in print. They might be:

- noticing the rhymes in a poem, song or nursery rhyme

- playing with language - saying strings of rhyming words, or coming up with rhythmic sentences like those in a book or song

- recognising and naming letters of the alphabet

- using some correct letters in writing their names, or writing their whole name correctly.

At this stage, it can be difficult to create effective planning that matches the children's levels of development and then moves them onwards. Often early work on letter sounds takes place in a context that fails to motivate children. A 'letter of the day' is an arbitrary choice by the practitioner and unlikely to spark interest in many children. Children will have no opportunity to use this new piece of knowledge, so many will forget it. Drilling young children in letter sounds through group work or worksheets will extend the children's knowledge of letter sounds, but research shows that they do not transfer this knowledge to real situations, like trying to read a word.

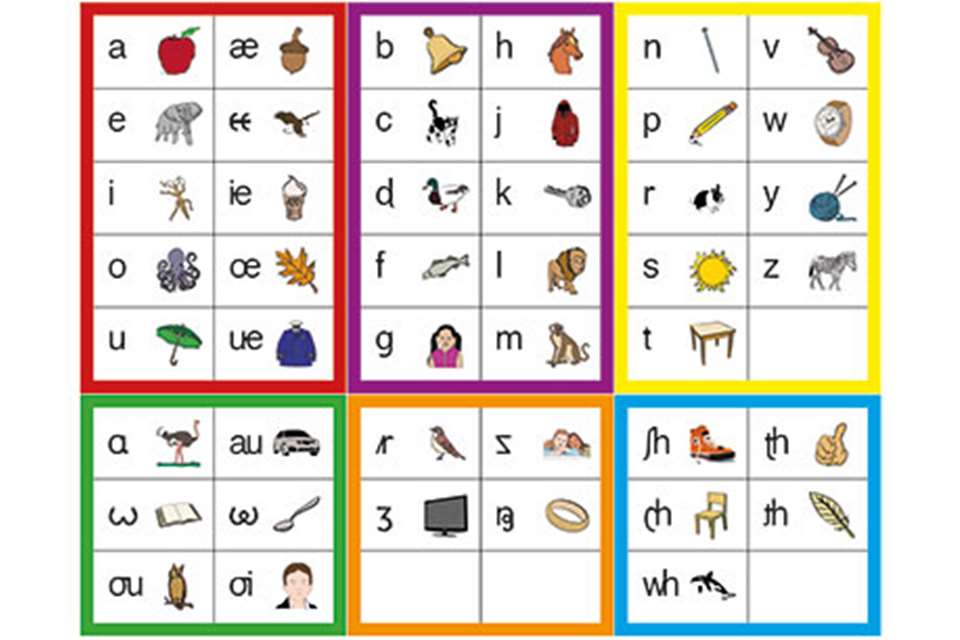

Very few children in the Foundation Stage can reliably hear the individual sounds (which are called 'phonemes') in a word. So, it will not be very useful for practitioners to start demonstrating to children how they can break down a word like 'cat' into its three phonemes c/a/t, or 'ship' into sh/i/p.

In any case, as the linguist Steven Pinker has clearly demonstrated, phonemes change according to where they are placed in actual words. Phonemes will not help you to sound out a word like 'place' or 'sign'. They have a role in teaching and learning about reading, but only when children know whole words and patterns in words.

However, young children can often hear the rhyming patterns in a set of words like cat-hat-sat-that. They can often hear how the onset (the first sound) changes and identify its sound. And they can often hear the rime (the sound of the rest of the word). If children can't hear the onset and rime, then practitioners can still extend their experiences through songs, poems and nursery rhymes.

Focusing on the detail of writing should be done sensitively. Adult interactions need to support children in feeling confident about applying their current understanding of letters and sounds to their writing. When young children are writing, they should be encouraged to experiment and not be afraid of making a mistake.

Support

- Play with language and encourage children to join in. Have fun making up a sentence about yourself like 'jumping Julian just jitters' and encouraging children to respond with their own inventions. Change nursery rhymes so that you now have 'Humpy Dumpty had a great ball', and again encourage the children's playfulness. You could use magnetic and foam letters while playing with the onset and rime to show the children how the letters that form the rime stay the same.

- Support children as they learn to write their names. You can teach children the names of the letters and their sounds, probably focusing in the beginning on just the first letter. Talk through how the letters are written with correct directionality. Children will be building upon their experiences of movement in other contexts like running outside or dancing. Practitioners across different settings need to discuss in detail how they name letters, describe their sounds and explain the motions for writing them. Otherwise children will receive inconsistent and contradictory feedback.

- Give children resources for playing with letters. Magnetic letters, computer programmes with letters and other resources can be a focal point for practitioners to talk to children about recognising and naming letters.

Window 3: growing use of specific knowledge about letters and sounds

At this stage children start to use their knowledge of letters and sounds to make sense of print or to express an idea in writing. They use this knowledge at the same time as they use other things they know, like recognising some whole words on sight, and their understanding about how books and stories work.

For example, a child might write something like 'gmt' for 'gone to the market', showing that they have a clear understanding of some of the letter and sound relationships needed to write that phrase.

It is important that practitioners' discussions and questions focus on and engage with children's thinking and their developing concepts. Ask questions like 'So what letter could you write to say that?' or 'That starts with "s". I wonder what that word says there?' Recognise that a child has mechanisms for understanding about print and letters. This encourages children to reflect on what they know. However, avoid getting in the way constantly of a child's search for meaning by stopping the flow of reading or writing to ask questions.

Support

- Ask carefully judged questions. For example, during shared writing with a child or a small group, ask, 'What letter do you think I will write for "dog"? What letter will I put next?' Shared writing involves the practitioner and the child collaborating on a piece of writing together, with the child contributing ideas and letters throughout.

- Write for the child. If a child has written a phrase like 'gmt', the practitioner could write the phrase correctly on a post-it note. The child could decide whether this should be stuck underneath their writing, or on the back of the paper. Discuss where both sets of writing have used the same letters, and why. Such an exercise can help children to build up lots of texts that they can read independently.

- Structure reading to focus the child on a particular strategy. Children need to be able to combine strategies in attempting to read a new word. Cover up a word with a post-it during the shared reading of a simple text, and ask the children to guess the word, so encouraging them to use their understanding of the text to establish the meaning of an unknown word. Move the post-it along to expose the first letter, so encouraging them to combine their understanding of the text with their knowledge of letters.

The great phonics debate

One of the hottest debates in the teaching of reading is about the role of phonics. It is now widely accepted that young children learning to read need to be taught about phonics - letters and their sounds. But how should practitioners plan for children's learning in this area?

Synthetic phonics

Some researchers and practitioners advocate the 'synthetic phonics' approach. This means that children are directly taught letters and sounds, and taught to blend the sounds together to create simple words.

Debbie Hepplewhite, newsletter editor of the Reading Reform Foundation, says, 'Children can rapidly and easily be taught the sound/symbol correspondences through multi-sensory programmes such as the well-researched Jolly Phonics scheme. After the introduction of the first six sound/symbol correspondences (s, a, t, i, p and n), the children put these to immediate use by listening for the sounds all-through-the-word for spelling, and by sounding out and blending (synthesising) the letters all-through-the-word for reading.

'This "synthetic phonics" approach (so-called because it emphasises blending for reading instead of guesswork or memorising whole words) is extremely inclusive, regardless of the children's backgrounds, gender, age or developmental-readiness.'

Whole-to-part phonics

Another group advocates the 'whole-to-part' method. They contend that children in the Foundation Stage find it difficult to hear individual sounds in most words, and question whether children can be taught to read by blending sounds together. For example, if you sound out the letters 'b-u-t' one by one as 'buh-uh-tuh' you are likely to hear the word 'butter'

and not 'but'. They advocate working with young children on a whole-word level at first, then drawing their attention to a simpler way of breaking words down to first and subsequent sounds. Further teaching about phonics takes place when children are beginning to think about letters and sounds in their early writing, when practitioners can put questions like, 'If you want to write mummy, I wonder what letter you will need first?'