Nursery Management: Inspection - In the frame

Pennie Akehurst

Tuesday, March 26, 2019

What is new in Ofsted’s recently published Education Inspection Framework, and what are the implications for managers in the PVI sector? Former council early years leader and consultant Pennie Akehurst reports

Download the PDF of this article

The new curriculum-focused inspection framework, to be launched from September 2019, has garnered headlines for reducing its focus on outcomes and the assessment processes which accompany them. Any move away from seeing children as units of data is surely positive – and the new inspection regime has been cautiously welcomed by the sector as a step in the right direction.

When we delve deeper, however, there are various changes which will have far reaching implications for the sector. Below I note some key changes and critique them.

‘Evolution not revolution’

The proposed changes build on the existing framework but place greater emphasis on the ‘what we do’ and ‘how we do it’. Although chief inspector Amanda Spielman has taken many opportunities to tell us that the changes are about ‘evolution, not revolution’, their significance should not be underestimated.

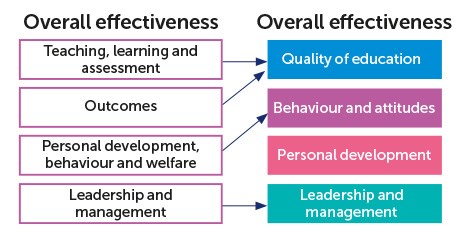

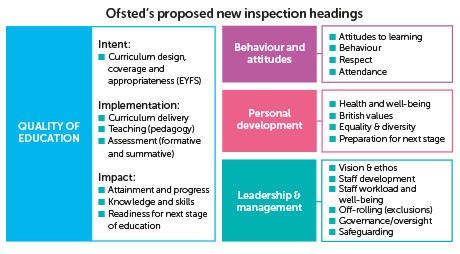

The most obvious changes are to the inspection headings, some of which have changed, or been split, (see below). They appear in both the EIF and the Early Years Inspection Handbook.

QUALITY OF EDUCATION

The most significant change is the move to place the curriculum at the heart of the inspection process. At multiple conferences, Ofsted has talked about getting to the ‘substance of education’; the proposals create a framework to judge the effectiveness of our provision by examining our intent, implementation and impact.

The term ‘cultural capital’ has also been introduced under Quality of Education with an expectation that we will be able to talk about what we teach, how we know our approach is right and how disadvantaged children benefit.

Leaders and managers will need to justify their pedagogy and curriculum design (what we teach and how we teach it).

My thoughts: We have never been asked to talk about this before and I wonder whether all settings will be in a position to rise to this challenge. Here’s why…

1. Qualifications – Many practitioners have accessed higher-level qualifications and professional development and are likely to feel confident to justify their approach. However, the minimum requirement for an early years manager is a Level 3. This A-Level equivalent qualification should prepare us to lead and manage provision; however, many managers would say this wasn’t their experience and that this did not prepare them to discuss pedagogy, philosophy and curriculum design.

2. Development Matters – I, along with many experts, including Julian Grenier and Jan Dubiel, have highlighted an overreliance on the widely used guidance Development Matters. This non-statutory guidance has become an integral part of countless recording systems. Many managers will think of this document as their ‘curriculum’, but it was only ever intended to be a ‘developmental pathway’ for children, therefore some managers may need additional support to meet this new requirement.

PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT; BEHAVIOUR AND ATTITUDES

Separating these two areas indicates a clear intention to focus in more depth on the impact that we, as practitioners, have on children’s learning and development.

Behaviour and Attitudes

It is good to see the Characteristics of Effective Learning so prominently featured, and inspectors will be required to consider how children are supported to learn while considering whether behaviour is contributing to positive attitudes to learning.

Inspectors will be asked to consider the age and stage of the children being observed.

My thoughts: The statements in the grade descriptors for Outstanding and Good have been written to reflect the behaviour and attitudes desired of children who are coming toward the end of their time at nursery, which has introduced a much higher level of subjectivity than has been seen in previous frameworks.

The criteria for ‘requires improvement’ and ‘inadequate’ focus on poor behaviour and attitudes to learning, which (again due to the subjective nature of the criteria) raises concerns about the approach that will be taken in areas of highest deprivation where, in some settings, there will be groups of children who continue to exhibit high levels of challenging behaviour despite the best efforts of the practitioners.

Personal Development

This is more reflective of the birth to five age range seen across different early years settings and is focused on the holistic development of the child.

LEADERSHIP AND MANAGEMENT

The ‘sources of evidence’ that indicated what inspectors should look at during an inspection have been removed from the current inspection handbook. How workloads are effectively managed also features.

My thoughts: I assume that the reason for this is to encourage leaders and managers to do things that are of importance to their setting rather than feeling that they need to use Ofsted guidance to generate a checklist of evidence for an inspection. After all, there has been much talk about reducing workload. But might this be counter-productive?

Many managers are confident in their systems and approach, but there are also managers who currently scour social media sites for any clues as to what Ofsted will be looking for. This is only likely to get worse if all possible ‘sources of evidence’ are removed. Less-confident or new managers may find themselves relying on social media rumour to ‘prepare’ for an inspection, in the absence of inspection guidance, which could result in a greater workload or misinterpretation.

Reference has also been made to the workload of staff, without much guidance to inspectors. Because the statement in the grading guidance is vague, this could mean that inspectors inadvertently get embroiled in conversations about, for example, whether staff should be paid additional time to update children’s files.

SAFEGUARDING

This remains a key area of focus, but as in the previous framework there is not a specific judgment for this area. Inspectors will continue to make a written judgement about the effectiveness of safeguarding arrangements under the leadership and management grading.

FINAL THOUGHTS

The motivation for the change seems to have arisen very much from the schools sector, as the inspection framework extends to secondary schools and further education colleges. Neil Leitch, chief executive of the Early Years Alliance, said it was ‘hard not to feel that early years, and the other areas of the education system weren’t much more than an afterthought’.

At the recent EIF launch in the West Midlands, a senior inspector said ‘having a proper conversation about curriculum takes time’.

He went on to say that inspectors have been in receipt of training over the past 18 months in preparation for the new framework. Is it, therefore, right to expect all settings to be able to respond to these changes in three to four months?

This doesn’t mean early years providers won’t be able to respond to these changes if given an appropriate lead-in time. The sector has shown that it is able to deal with fast-moving policy changes.

I am also concerned about the level of subjectivity that has been introduced. How will complex, detailed, value-laden judgements about an early years curriculum be made consistently and fairly, as the National Education Union has also pointed out? It also provides significantly more scope for misinterpretation on both the part of an inspector and management teams, who will continue to use the Early Years Inspection Handbook as a self-evaluation framework. This is of concern because no new system/framework is ever implemented with consistency from day one.

It will take time for this new way of working to embed, but meanwhile a setting could receive an ‘incorrect’ inspection judgement that could lead to the loss of local authority funding (inspection outcomes are directly linked to places), which could potentially close them.

THE NEW DOCUMENTS

In January, Ofsted published the draft Education Inspection Framework (EIF) alongside separate inspection handbooks for early years, schools and the education and skills sectors. The Early Years Inspection Handbook, interprets inspections under the new framework for the early years sector.

The EIF sets out how Ofsted intends to inspect in the future and will replace the Common Inspection Framework (CIF).

In 2015, Ofsted introduced the CIF. This was the first time that all of the inspection remits had been brought together under a single framework. The rationale was to provide a consistent approach and ensure a greater level of comparability across the different types of education provider.

So why the change? The perfect framework was never going to be achieved on first attempt. Harmonising the frameworks was complex and the CIF’s implementation was closely monitored to establish its successes and limitations, which brings us to the current day.

FURTHER READING

Consultation closes at 11.59pm on 5 April, with revised documents to be published in May. See https://bit.ly/2Hgu6hL

Nursery World conference

Get ready for the new Ofsted inspection framework at our conference on 9 July