A Unique Child: Trauma - After the event

Erica Brown

Monday, September 4, 2017

Following a traumatic event, children are particularly vulnerable to adverse reactions. Erica Brown examines the kind of responses they may have and how adults can help children through them

Traumatic events are rarely off our TV screens and have been witnessed on our streets in recent months, from the Grenfell tower fire to the Manchester terrorist attacks. Such events often strike unexpectedly, turning everyday life upside down and destroying the belief that it could not happen to us.

Trauma is a normal human response but one that is also complex, incorporating a myriad of emotional, behavioural and cognitive reactions. This is particularly true for children, though little is known about young children’s individual responses to such events, or why some children are more vulnerable to experiencing traumatic stress than others.

Not all children will have adverse reactions to traumatic events that they have experienced directly or seen in the media. For some, reactions will be minimal or short-lived, though many are likely to experience anxiety, fear and phobias, in the immediate and perhaps long term.

SEVERITY

Seeing disturbing images of dead or severely injured people, as well as experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event, can all trigger a severe reaction in a child. The severity of the response is largely determined by the seriousness of the event itself and the degree and duration of a child’s exposure to it. This will include factors such as:

- the severity of harm or threat to the child’s life or that of their loved ones

- the suddenness of the event – such as the destruction of the child’s home or a well-known building within their community

- the degree to which the child was rendered powerless

- whether the child was alone or with other people

- the possibility of the event reoccurring, and the intensity and proximity of exposure to disturbing images.

In some cases, the nature of the event seems to determine how children respond.

If the trauma involved heat, noise or darkness, children’s reactions may be more intense.

REACTIONS

Although it is unlikely that children will experience all the following changes in behaviour, many will present with observable signs of restlessness, a heightened alertness to danger and irritability or outbursts of anger and temper tantrums.

Common responses to a traumatic event often emerge at night time, with many children afraid of the dark or being alone. While some struggle to get to sleep, others will wake frequently and may experience night terrors.

Other common reactions also include:

- panic attacks

- a regression of previously acquired skills

- refusing to go to school or tonursery

- raised levels of anxiety

- under-achieving at school

- separation anxiety

- clinging behaviour.

Case study: Sacha

Sacha was four years old when she was woken in the middle of the night to the sound of loud banging and shouting. She got out of bed and stood at the top of the stairs where she witnessed first-hand her father being handcuffed and escorted out of the front door by uniformed police officers.

Six months later, her school had arranged for a local police community support officer to visit as part of a ‘People Who Help Us’ project. When the policewoman walked into the classroom, Sacha covered her ears and screamed, ‘Don’t take me!’

Sacha was reassured by her teacher, who texted her mother. She came to the school immediately and sat in the classroom holding Sacha while the police officer talked to the children.

Case study: Jason

Imagery of the event seems to be one of the recurring effects of trauma. Jason, aged five years, was asleep the night his home caught alight. He recalls: ‘I can smell the feeling of the house burning. My mum screamed for me. The fire engines came and I saw everything eaten by the fire. There were big bubbles coming out the sofa like a volcano.’

Four years after the event he cannot tolerate the smell of toast cooking, the sound of a fire engine siren or media coverage of fires.

Case study: Rory

Many children will experience a phase of denial and numbing, when they feel that the situation could not have happened. After this, a child may be confronted with intrusive, repetitive recollections of the event.

Rory, aged three, was on a camping holiday by the sea with his family. One night a spring tide battered the sea wall at the bottom of the campsite causing local damage and washing away beach huts. For the remainder of the holiday, Rory insisted on sleeping with his parents ‘in case the water comes to get us’.

SEARCHING FOR MEANING

Children need to make sense of their experiences and so will seek to understand both the traumatic event and their feelings.

Children need to make sense of their experiences and so will seek to understand both the traumatic event and their feelings.

Many children who have been the victims of trauma believe they were in some way responsible for what happened. Thus, a child who has witnessed a violent attack either in their home or in the environment may believe their behaviour contributed to the event. Others may be confused about why they are frightened, especially if they see other people apparently unaffected. Adults need to be open and honest and admit that sometimes there is no rational explanation for what happened.

Very young children may not have the language to describe how they feel and may battle with the intensity of their emotions. They may never have experienced intense emotions before, and it is not unusual for them to attempt to repress these unknown feelings. For them, the world has become unfamiliar and frightening.

Case study: Rabie

Rabie’s mother had a stroke while she was driving with Rabie and her two siblings. The car went out of control and crashed into a bus. Miraculously, the children were unhurt, there were no casualties among the bus passengers and Rabie’s mother recovered.

However, just before the crash, Rabie had given her mother a sweet that she attributed to the cause of the stroke. She needed constant reassurance from her family that she was not responsible for the accident. It was only when her dad asked her to share her sweets with him on a car journey that she was able to recover from the experience.

RE-EXPERIENCING THE EVENT

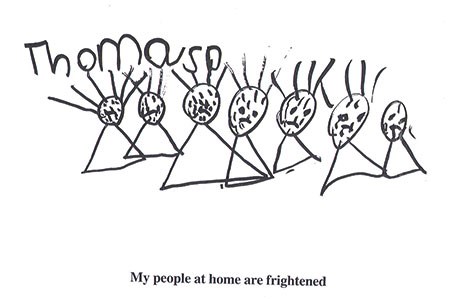

Children are likely to become distressed when aspects of events remind them of their traumatic experiences. They may also relive their experiences in nightmares, flashbacks and in play, such as in role play or in their paintings and drawings.

CAPACITY TO COPE

How well a child copes with a traumatic experience is dependent on several inter-relating factors – the child’s own cognitive ability and capacity to express their emotions, and the level of stability and support that they enjoy within and outside the home, including the presence of primary carers and significant others in the child’s life and familiar routines.

How well a child copes with a traumatic experience is dependent on several inter-relating factors – the child’s own cognitive ability and capacity to express their emotions, and the level of stability and support that they enjoy within and outside the home, including the presence of primary carers and significant others in the child’s life and familiar routines.

When the trauma has stemmed from disturbing imagery, the child’s ability to cope will also be determined by the level of media coverage of the event.

SUPPORTING CHILDREN

- To support children in your setting who have experienced trauma:

- Identify children who may be potentially at risk.

- Reassure children that their response is normal.

- Acknowledge the shock of what has happened to them.

- Encourage the child to express how they feel.

- Work closely with other professionals who are supporting the child’s family.

- Keep routines as normal as possible and encourage the child to join in activities with their peers.

Case study

After seeing images on TV of the terrorist attack in Manchester earlier this year, twin brothers aged six asked their grandma, ‘Why did the bad man do it?’ Their grandma acknowledged the boys’ confusion and answered as honestly as she was able, validating their concern. She told them that she didn’t understand the motives of the terrorist and said that even grown-ups cannot explain.

The boys went to school the following day and repeated what their grandma had said during a circle-time activity. Several of the other children spoke about what they had seen on their televisions. The teacher encouraged the children to talk and she organised an activity where the class drew faces which expressed emotions.

At the end of the day, the teacher met parents and explained how she had responded to the children’s concerns.

MORE INFORMATION

Erica Brown MA MEd FRSA is a senior research fellow at the University of Worcester and author of Life Changes: Loss, Change and Bereavement for Children Aged 3-11 Years Old