parents, and practitioners, to advance the child's oral language. Joan

Kiely explains the method and its importance.

Young children who can express themselves well and have a good store of oral vocabulary are stepping into the world of learning with a great advantage. They can better understand themselves and others, they can better make their needs known, they can better interpret what is going on around them and they can better share their experience of the world.

One way to develop children's oral language is to read stories to them and chat about the story as you read it. By simply sitting together in a quiet space with a child, cuddling up for a few minutes and focusing on a story together, parents and early years practitioners are not only improving child-adult relationships but familiarising the child with a type of language that is not heard in everyday conversation. This is referred to as decontextualised language and is important for a child's development.

RESEARCH FINDINGS: ORAL LANGUAGE AND HOME READING

Good oral language skills develop good readers

Research shows that there is a relationship between oral vocabulary size and phonological awareness (ability to differentiate between sounds) in emergent readers and between oral vocabulary and comprehension in older readers (Whitehurst and Lonigan, 2002). This means that good oral language ability puts a child on the path to being a good reader.

Unfortunately, not all children are in a position to benefit from rich early language experiences. Research indicates that children from disadvantaged socio-economical backgrounds are behind their more advantaged peers in verbal and other cognitive abilities by the time they enter school (Hart and Risley, 1995; Ramey and Ramey, 2004). It is important, then, that parents and other adults do what they can early in children's lives to support language development.

Children are influenced by their parents' attitudes to reading

Children love to imitate what they see happening around them. If parents are seen to read in the home, this sends a powerful message to children about the importance of reading. Research tells us that home literacy behaviours are predictors of various developmental and educational outcomes for children (Kassow, 2006).

Home literacy behaviours include activities such as observing parents reading (books, magazines, newspapers, bills), writing (shopping lists, menu planning, letters), visiting the library with parents and engaging in shared book reading with parents (Kassow, 2006).

The age that parents establish a home reading routine predicts their child's oral language skills

Debaryshe (1993) found that the age that home reading routines begin is the most important predictor of children's oral language skills. Parents can begin to read to their child while they are still in the womb. The child will get used to the rhythm and pattern of the mother's voice and will develop early listening skills even though they do not comprehend as yet.

Babies whose parents or carers read to them are likely to feel positive about books and will associate books with warm relationships and bonding experiences. In addition to this, they will pick up important information about books - for example, how to turn pages, look at pictures and point at them.

When reading to a baby, it is a good idea for the adult to alter their tone and pitch, to inflect the voice in order to stimulate the baby's interest. Repeated readings of the same book is also recommended because it helps the baby build language skills (Biemiller and Boote, 2006).

Research indicates that children who were read aloud to before they started school scored higher on national literacy tests than children who had not been read to (Mullan and Darragnova, 2012). It makes sense, therefore, to encourage parents to read stories to their children from an early age.

Introducing decontextualised language is important to a child's development

Decontextualised language is a form of language that is regularly employed in the learning environment of school and is important for children's academic development. It is described as language that is not based on the here and now or on the immediate physical environment, but is more abstract.

For example, young children might find it easy to express a need or to talk about a physical object in front of them - for example, they might say, 'Give me that teddy' - but decontextualised language challenges them to use extended discourse such as explanations, narratives and pretend play (Demir, Meadow, Levine and Rowe, 2010).

When an adult is reading a story to a child, there are opportunities to discuss characters' motives and to speculate on developments in the plot. These exercises require the use of decontextualised language.

Story facilitates the development of decontextualised language because story is life experience in an abstract form. 'Narrative fiction offers models or simulations of the social world via abstraction, simplification and compression' (Mar and Oatley, 2008).

ORAL LANGUAGE AND DIALOGIC STORY READING

Reading stories aloud to children is one of the most highly recommended activities for supporting their language and literacy development (Beck and McKeown, 2001). Dialogic story reading is a particular method of reading to a child that has been found to be the most effective method to develop children's oral language.

Dialogic reading is the practice whereby a child and an adult share a picture book, and focus on the picture book and the story through talk (Whitehurst and Lonigan, 1998). When most adults share a book with a pre-school child, they read and the child listens. In dialogic reading, the adult helps the child become the teller of the story. The adult becomes the listener, the questioner and the audience for the child (Whitehurst, 2002).

Research studies indicate that a dialogical approach to reading - when the child has an active part in the reading experience, talks about the story and asks and answers questions about the story - is more effective in developing oral language than when adults just read the book to the child with little or no interaction (for example, Trivette and Dunst, 2007; Hargrave and Senechal, 2000).

Dialogic story reading not only develops oral vocabulary but also more complex language skills such as grammar, listening comprehension, and the ability to form an argument and to elaborate (NELP, 2008). These complex language skills are what make a difference to reading skills in the middle grades in school.

Dialogic reading helps children to:

- use more words

- speak in longer sentences

- score higher on vocabulary tests

- demonstrate overall improvement in expressive language skills

(Doyle and Bramwell, 2006; Huebner and Meltzoff, 2005; Hargrave and Senechal, 2000; Huebner, 2000).

DIALOGIC READING: STEP BY STEP

Use PEER and CROWD

Dr Grover Whitehurst is an American developmental psychologist who originally created the dialogic reading programme in the early 1990s. Whitehurst proposes a reading technique called the PEER sequence, which is a way of interacting between the adult and the child. The PEER sequence is an acronym for the following.

- Prompts the child to say something about the book

- Evaluates the child's response

- Expands the child's response by rephrasing and adding information to it

- Repeats the prompt to make sure the child has learned from the expansion.

An example of an interaction between an adult and a two-year-old child might go something like this.

The parent points to a cat in the book and says, 'What is this?' (visual prompt). The child answers 'A cat'. The adult says, 'That's right, (the evaluation); a black cat (expansion). What is it again? It's a _____ ___ (repetition)' (Whitehurst, 2002).

The adult might go on to enquire, 'Who do we know that has a cat?' The child might respond by talking about a relative or neighbour. This important strategy supports the child in relating the story to their life experience. Dr Whitehurst calls it a distancing prompt.

In all, he describes five prompts or comments to encourage the child to say something, and describes these by using another acronym called CROWD:

- Completion prompts You allow the child to finish your sentence. The child understands what to do by the upward inflection of your voice towards the end of the sentence and the blank left by you. For example, 'Molly knew Patch was happy because he wagged and wagged his ______.'

- Recall prompts These prompts happen when you want to re-read a book that you have already read with the child. You might ask the child, 'Can you help me remember where Molly brought Patch for a walk?' This encourages children to respond and makes the relationship more egalitarian if you are recalling together, musing and mulling over matters together, rather than putting the child on the spot by asking a direct question.

- Open-ended prompts Dr Whitehurst says that these prompts tend to focus on the pictures in books and they work best if the pictures are rich in detail. The idea behind open-ended prompts is to encourage a narrative flow from the child. Just like with the recall prompt above, it is better to speculate with the child than to ask a direct question (Powell and Snow, 2007). So instead of saying, 'What do you see here?' it might be more beneficial or productive to say something like, 'Mm, I wonder what is going on here ...' then leave a pause. Hopefully the child will fill the gap.

- Wh- prompts These are 'what', 'where', 'when' and 'why' questions. These are not open-ended questions, but they serve a good purpose, in that they support children in deepening their focus.

- Distancing prompts These require children to make a link between the book and the real world. For example, when Hansel and Gretel get lost in the woods, the adult might recall with the child a time they got lost in a department store. Story helps to build identity. By empathising with characters and comparing their dilemmas with the child's life experience, it helps to make the story meaningful for the child and to find resonance for their life.

Don't interrupt the first reading of the story too much

The prompts described here are likely to break up the flow of the story, so it is not advisable to use them during the first reading of the story to the child. Biemiller and Boote (2006) tell us, for example, that children dislike interruptions for word explanations when the story is being read for the first time. However, they don't mind interruptions during subsequent readings.

After several readings and explorations of the book together over three to five days, the child should begin to take over the story and the adult reader is often told, 'I'll say it'.

The repetition of the story is important for younger children (two- to six-year-olds) because it builds their vocabulary. In fact, research by Childers and Tomasello (2002) tells us that a child needs to hear a word 20 times before it becomes part of their expressive vocabulary.

However, Biemiller and Boote (2006) warn that repeated readings of a story, though beneficial in the case of younger children, bring about a 14 per cent decrease in vocabulary for older children (seven- to eight-year-olds).

Follow the child's lead

A child's vocabulary is particularly advanced when parents or other adults talk about the focus of the child's attention.

A corollary finding is that children learn fewer words when their parents try to re-direct their attention to objects and matters not of interest to them (Harris, Golinkoff and Hirsh-Pasek, 2011).

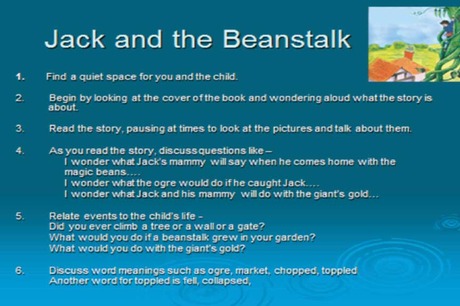

Be guided by the tip sheet

Above is an example of a tip sheet prepared for parents to assist them in reading the story of 'Jack and the Beanstalk' to their child.

It is not intended to be prescriptive because the advice is to follow the child's interest in the story.

TRAINING IN DIALOGIC STORY READING

Research tells us that if parents are given training or coaching in dialogic reading strategies, they tend to continue to use those strategies. Huebner and Payne (2010) provided the first evidence that brief instruction in interactive reading has an enduring effect on parents' reading style. Parents who were taught to use dialogic reading behaviours when their children were two or three years old continued to use this reading style more than two years later.

Moreover, research tells us that giving parents specific literacy coaching advice in relation to how to work with their children works better than giving general literacy advice to parents (Senechal and Young, 2008). Dialogic story-reading strategies are an example of specific literacy coaching advice.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Research indicates that dialogic story reading is an effective way to develop a child's oral language, particularly decontextualised language.It is important that there is fidelity to the strategies outlined here because use of the strategies is what makes story reading dialogic and is therefore what facilitates the development of children's oral language.

However, in our efforts to 'do it properly', we must bear in mind that unless the child is enjoying the story and the experience of interacting around the story, our struggle to improve oral language skills will be in vain.

It is of paramount importance that story reading is an enjoyable experience for the child. Enjoyment of reading generates motivation. If motivation to read exists, it is likely that children will learn to read without stress. They will also develop habits of reading that will advantage them greatly as learners and bring both added joy and richness to their lives.

Joan Kiely is a senior lecturer in Early Childhood Education at Marino Institute of Education, Dublin

REFERENCES

- Beck, I & McKeown, M (2001). 'Text talk: Capturing the benefits of read-aloud experiences for young children'. The Reading Teacher55(1).

- Biemiller, A & Boote, C (2006). 'An effective method for building meaning vocabulary in primary grades'. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 44-62. doi:10.1037/00220663.98.1.44

- Campbell, (1999). Handbook of Language & Literacy development: A roadmap from 0 to 60 months.

- Childers, JB, & Tomasello, M (2002). 'Two-year-olds learn novel nouns, verbs, and conventional actions from massed or distributed exposures'. Developmental Psychology, 38(6), 967.

- Debaryshe, BD (1993). 'Joint picture-book reading correlates of early oral language skill'. Journal of Child Language, 20(02), 455-461. doi:10.1017/S0305000900008370

- Demir, E, Levine, SC, & Goldin-Meadow, S (2010), ‘Narrative skill in children with early unilateral brain injury: a limit to functional plasticity’, Developmental Science, 2010, 13:4, 636-647.

- Doyle, BG & Bramwell, W (2006). 'Promoting emergent literacy and socio-emotional learning through dialogic reading'. The Reading Teacher, 59(6)

- Hart, B & Risley, T (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young american children. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing

- Hargrave, A & Senechal, M (2000). 'A book reading intervention with pre-school children who have limited vocabularies: The benefits of regular reading and dialogic reading'. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(1), 75-90.

- Harris, J, Golinkoff, R & Hirsh-Pasek, K (2011). 'Lessons from the crib for the classroom: How children really learn vocabulary'. In S B Neuman & DK Dickinson (Eds), The handbook of early literacy research (volume 3 ed, pp49-65) Guildford Press.

- Huebner, CE (2000). 'Promoting toddlers’ language development through community-based intervention.' Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21, 513-535.

- Huebner, CE & Meltzoff, AN (2005). 'Intervention to change parent–child reading style: A comparison of instructional methods'. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 26(3), 296-313 doi:http://dx.doi.org.remote.library.dcu.ie/10.1016/j.appdev.2005.02.006

- Kassow, DZ (2006). 'Parent-Child Shared Book Reading Quality versus Quantity of Reading Interactions between Parents and Young Children'. Talaris Research Institute 1(1).

- Kelleher, E (2005). Parental involvement in the language development of preschool traveller children through the use of storybooks. (unpublished master’s thesis) St. Patrick’s College of Education, Dublin City University.

- Mar, R & Oatley, K (2008). The function of fiction is the abstraction and simulation of social experience. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(3), 173-192.

- Mullan, K, & Daraganova, G (2012). 'Reading: The home and family context'. Paper presented at the Children's Reading in Australia: The Home and Family Context. 12th Australian Institute of Family Studies Conference: Family and Trajectories, Melbourne, VIC, Australia.

- National Early Literacy Panel (2008). Developing early literacy: Report of the national early literacy panel 2008. Washington D.C.: National Institute for Literacy

- Powell, M. B., & Snow, PC (2007). Guide to questioning children during the free-narrative phase of an investigative interview. Australian Psychologist, 42(1), 57-65. doi:10.1080/00050060600976032

- Ramey, CT, & Ramey, SL (2004). 'Early learning and school readiness: Can early intervention make a difference?' Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 50, 471-491.

- Sénéchal, M & Young, L (2008). 'The effect of family literacy interventions on children’s acquisition of reading from kindergarten to grade 3: A meta-analytic review'. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 880-907.

- Whitehurst, Grover J (Russ) (2000). 'Dialogic Reading for Preschoolers'. Presentation at the Wisconsin Literacy Showcase. Oshkosh, WI.

- Whitehurst, G, & Lonigan, C (2002). 'Emergent literacy:Development from prereaders to readers'. In Susan B. Neuman, David K. Dickinson (Ed), Handbook of early literacy research volume 1 (pp. 11-29.) The Guildford Press.