Toxic Childhood author calls for kindergarten until seven

Monday, February 8, 2016

A former head teacher has called for a Nordic-style statutory kindergarten stage, claiming that our youngest schoolchildren are ‘trapped’ by a damaging formality that began with the British Empire.

A former head teacher has called for a Nordic-style statutory kindergarten stage, claiming that our youngest schoolchildren are ‘trapped’ by a damaging formality that began with the British Empire.

Sue Palmer, author of parenting book Toxic Childhood, is campaigning for three- to seven-year-olds to be educated ‘free from the pressure of the formal school system and educational target-setting’.

The Edinburgh-based writer, who is currently focusing her efforts on changing the Scottish system, claims 19th Century moves by the English parliament to send younger children to school have left a harmful legacy of an increasing ‘schoolification’ of the early years.

The author suggests this mindset has been bolstered by prejudice against child-centred learning and resulted in the erosion of crucial time at play.

‘It’s a historical accident and political prejudice,’ said Ms Palmer.

‘In the 70s and 80s, the child-centred approach was taken to the extreme. That put the whole idea of left-wing educational loonies in the politicians’ minds.

‘Now, anything that comes from the educational establishment is considered to be part of a left-wing, loony blob,’ she added, referencing former education secretary Michael Gove’s attack on the critics of his reforms.

The literacy specialist added, ‘We’re trapped by history and tradition. In 1870, the English parliament chose an early school starting age so that children’s mothers could provide cheap labour in factories.

‘Scotland followed suit, and ever since we’ve taken it for granted that formal education must start at five.

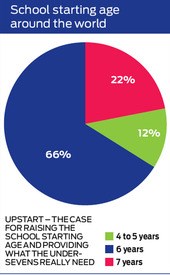

‘Only 12 per cent of countries worldwide start children at school so early – and all are ex-members of the British Empire.’

In September last year, the Scottish Parliament announced that it will be introducing statutory primary school testing from Year 1. But Ms Palmer argued the Scottish system was ‘more sensible and developmentally appropriate’ than the English one.

Her campaign, called Upstart, precedes the June publication of her new book, with the same name, which sets out her case for ‘raising the school starting age and providing what the under-sevens really need’ (see box, right).

She added, ‘There’s so much research on giving children the time and space to play for their physical, social, emotional and cognitive development. Play is the in-born learning drive. All children benefit from having longer in the play-based environment.’

Ms Palmer argues that a kindergarten stage could even address economic disadvantage and a widening achievement gap between girls and boys.

‘They always say, “We want to do the best for everybody,”’ she said. ‘But I find that parents who’ve read up on this are getting more and more concerned about the early start.’

There is an initial academic advantage to starting school earlier, she claimed, which ‘washes out’ by the age of 11.

She added, ‘Children from disadvantaged backgrounds are arriving at school with a huge deficit in terms of their capacity to settle down. Play-based development which treats them as individuals, helps their self-regulation and language skills – things they need for school – will mean we level the playing field.

‘As it is, we’re disadvantaging them further. We can teach them like parrots doing phonics. If they’re socially and emotionally unadjusted, by the time they’re 11 they’ll be no better than children who started at seven – they’ll have less resilience and then things start to fall apart.’

She added that the Upstart campaign had already attracted interest and that its launch meeting in Dundee earlier this month attracted 300 people, mostly parents.

HOW DID WE GET HERE?

This is an edited extract from Upstart: The case for raising the school starting age and providing what the under-sevens really need, by Sue Palmer.

Why school starts so early in English-speaking nations, how politicians are ‘schoolifying’ the pre-school years and why this is damaging

Starting school is a big moment in anyone’s life. Indeed, in today’s highly competitive educational environment, it’s one of the biggest moments of all – early success or failure at school is likely to affect every aspect of a child’s future existence. So it would be reassuring for parents to know that the rationale underpinning the school starting policy is governed by careful consideration of young children’s needs, backed up by well-established educational research, and endorsed by experts.

Unfortunately, it isn’t.

A VERY BRITISH STORY

I n fact, starting ages for formal schooling around the world were chosen by politicians, as opposed to educational experts. And even for most politicians, the thought of putting four- and five-year-olds into a formal school environment seems to have been unpalatable. During the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, the governments of 66 per cent of countries chose six as the starting age, while in 22 per cent (including some of the most educationally successful nations) they preferred seven years old.

n fact, starting ages for formal schooling around the world were chosen by politicians, as opposed to educational experts. And even for most politicians, the thought of putting four- and five-year-olds into a formal school environment seems to have been unpalatable. During the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, the governments of 66 per cent of countries chose six as the starting age, while in 22 per cent (including some of the most educationally successful nations) they preferred seven years old.

That leaves only 12 per cent of countries worldwide where children start school at five or younger. Interestingly, this 12 per cent consists of the four nations of the United Kingdom, and a selection of its ex-colonies and protectorates, including Australia. In effect, every wide-eyed child around the world who starts compulsory schooling before six is the great-great-grandson or daughter of the British Empire.

It is on the record that the most important considerations in 1870 were economic ones, determined by the needs of big business rather than small children. Child labour had recently been outlawed, so elementary education was considered ‘of great utility’ for keeping poor children off the streets while their mothers went to work. The early starting age was also a sop to irate employers, who had recently been deprived of numerous cheap, biddable workers: the sooner school started, the sooner factory fodder could be released at the other end.

The early start policy was quickly absorbed into the national consciousness. And once children were out of sight in their primary schools, they remained out of mind, so for over a hundred years what happened to them there was of little interest to politicians or the general public. Even when, in the middle years of the 20th Century, people began to ask questions about the efficacy of state schooling, solutions were always sought in changes to secondary and tertiary education.

By the late 1980s, working mothers were, as in Victorian times, once more the norm and the English Government offered to grant free ‘early years education’ for four-year-olds – an apparent boon for both families and employers. Since schools are paid per capita, most primary head teachers welcomed these tiny new recruits – the policy was affectionately known as ‘Bums on Seats’ –and an even earlier start to education was rapidly normalised. Within a decade or so, the overwhelming majority of English four-year-olds were in Reception classes, including ‘summerborns’ who’d only just turned four.

EVERYONE OUT OF STEP BUT US

Why, then, did the rest of the world opt to start schooling at least one year (and up to three years) later? When the fashion for state-provided education began in Europe in the 19th Century, there was no scientific evidence on which to base the decision. There was, however, a long history of education for more privileged children, which had traditionally begun around seven years old.

When the science of developmental psychology began to emerge, it provided scientific evidence that the first seven years or so of cognitive development is qualitatively different from later stages. Ever since, there has been a significant difference between the ethos of early years educational systems worldwide and those of traditional schooling.

There are many different names for systems of early years education around the world – nursery school, pre-school, playschool – but I’ve chosen to use the Froebelian term ‘kindergarten’, partly because it avoids the term ‘school’. The younger children are, the more the educational emphasis has to be on helping each one develop various physical, emotional, social and cognitive abilities – as opposed to teaching skills and knowledge, as in traditional schooling systems.

THE POWER OF PLAY

Kindergartens stress the importance of play, which is the natural means by which young human beings have always explored, experimented and developed understanding of their social and material environment. Along with adult support and guidance, children’s own active, self-directed play is now widely recognised as critical to the development of:

physical co-ordination and confidence, the ability to focus attention and control behaviour

emotional strengths, including a can-do attitude, resilience and the patience to pursue long-term aims rather than immediate rewards

social competence, such as getting along with their peers, working collaboratively in a group and communication skills

cognitive capacities, such as the use of language to explore and express ideas, and a ‘common-sense understanding’ of the world and how it works, which underpins mathematical and scientific abilities.

To enrich and support children’s own play, kindergarten education usually includes frequent opportunities for children to be outdoors in natural surroundings, and stresses the age-old (and fundamentally playful) human activities of song, dance, story-telling, art and drama. All this is combined with adult-led activities (of growing length and complexity as the kindergarten years go by), designed to lay firm foundations for children’s future success at school. But developmentally based kindergarten education isn’t merely about ‘schoolreadiness’. It’s about readiness for life in general.

To enrich and support children’s own play, kindergarten education usually includes frequent opportunities for children to be outdoors in natural surroundings, and stresses the age-old (and fundamentally playful) human activities of song, dance, story-telling, art and drama. All this is combined with adult-led activities (of growing length and complexity as the kindergarten years go by), designed to lay firm foundations for children’s future success at school. But developmentally based kindergarten education isn’t merely about ‘schoolreadiness’. It’s about readiness for life in general.

- Upstart is published on 16 June (Floris Books, (£9.99). Download a Chapter 1 sampler at http://bit.ly/1WZAszi