Feeling fascinating

Kelly Brooker and Carrie Brown

Monday, July 8, 2019

How three settings in London used their pupil premium funding to support children’s sense of self through drawing and talking.

Busy lives, bustling environments and dwindling budgets can make it difficult to give children the individual time and attention they need. For this reason, we decided to use our pupil premium funding (PPF) to buy back time for our children – time to be listened to, time to talk, time to draw, time to be in the company of an adult who has no agenda, other than to be interested and available.

As a federation of three nursery schools in Barnet, north London – the Barnet Early Years Alliance (BEYA) – we combined our PPF to employ a skilled early years teacher to work two days a week across the three schools to carry out a ‘drawing and talking’ project.

Thirty-six children across the federation are entitled to PPF, and under the project, each child has a minimum of eight drawing and talking sessions with the teacher.

PRINCIPLES

The project is based on two main pedagogical principles:

Drawing is one of the most effective methods of communication for young children. Drawing can be an extremely powerful vehicle for children to communicate their ideas, re-visit, re-live and re-present significant events, feelings or memories. There is nothing more open-ended than a blank piece of paper, which means that when a child draws, the adult gains a valuable insight into their thinking. As is argued by Wright (2007), ‘Artistic communication is the literacy par excellence of the early years of child development.’

Children develop their sense of self from social interactions with other people. Gerhardt (2004) reflects that, ‘It is positive looks which are the most vital stimulus to the growth of the social, emotionally intelligent brain.’

Similarly, O’Brien (2011) argues, ‘In much the same way as we each learn to define the meaning of things in our environment, we learn about who we are through observing the responses of others to us as objects.’

AIMS

The main aim is to facilitate a genuinely positive experience between the adult and the child by simply giving children our whole attention, listening and responding to them as they draw and talk. The provocation for communication is the marks that children make on the paper. In a multi-modal way, the drawing leads the talk and the talk in turn leads the drawing.

It is a fascinating window into the minds of young children and how they think. As Anning and Ring (2004) argue in the preface of their book Making Sense of Children’s Drawings, ‘drawing offers a powerful vehicle for hearing what young children are telling us’.

IN PRACTICE

When the child has developed familiarity and trust with the adult through play in the nursery, they are invited to a quiet area to do some drawing. The sessions may be 1:1 or in small groups of two or three. Each child has their own A3 portfolio of paper and draws on just one page each session.

The portfolio is kept safe at nursery and a blank page is waiting for the child at the beginning of the session. The children are provided with felt-tip pens and are invited to draw whatever they would like to on the page. The session lasts until the child has decided they have finished – for some children this is five minutes, for others it is 40 minutes.

ADULT ROLE

Being above ratio and with no other responsibilities in the nursery, the teacher has no time limitations or distractions and can offer children their whole attention.

The role of the adult is to allow children to lead the sessions. They listen and respond with interest to what the child communicates. While this may sound simple, it requires great skill and reflection; deciding when to make comments, ask questions or stay silent.

The children communicate with the teacher in a variety of ways: some are highly verbal, initiating conversation, asking questions, attaching meaning to their marks as they draw, describing their ideas and experiences in detail. Others draw quietly or silently, absorbing the silence, considering each new mark, perhaps choosing not to explain them at all. The same child may respond differently each week depending on how they are feeling.

The adult is respectful of the child’s style and mood and mirrors their behaviour. If the child is quiet, so is the adult; if the child is animated, the adult responds with matched enthusiasm. This helps to create a safe space in which no expectations or pressure are placed on the child. This responsive interaction has helped some children to make dramatic progress.

CASE STUDIES

Emre

For one child, Emre, his key person noticed how the sessions were helping him to manage his emotions. ‘Emre had been finding it difficult to tell me about how he felt, emotionally,’ they explained. ‘I knew he had good language skills, by observing him with other children, but when he felt sad or cross he shut down and excluded himself from the group. When I first witnessed Emre having a talking and drawing session I was amazed to see how much he opened up. I couldn’t hear the conversation, but it was so animated.

‘Emre now uses drawing as a form of self-regulation when he arrives at nursery and isn’t feeling happy – independently finding pen and paper. He is now often happy to tell me when he is angry or sad and will have a conversation with me about how we can work together to help.’

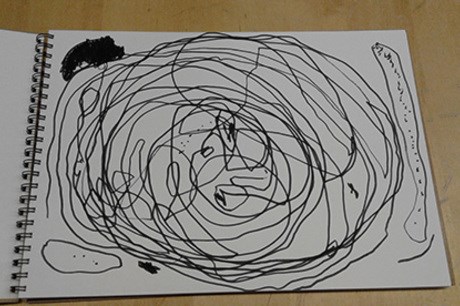

In the drawing (shown left), Emre creates a story about lava. His rotational marks represent the action of running away from the lava. The character that Emre imagines running away is from the game Roblox: ‘He is running this way and that way – arghh!’ Emre notices the ‘emergency exit’ sign in the room and asks if the figure on the sign is running away from lava. The closed shapes on the right and bottom left corner are playgrounds, the dots are people inside them.

Julie

For Julie (above), the drawing and taking sessions are a joyful and sensory experience. Each week, she has approached the blank page with a broad smile and eagerness to begin. She has a range of drawing styles: sometimes she is silent, adding careful detail, her nose almost touching the paper; often she is wildly expressive, laughing loudly, using huge rotations and arcs, filling her page (sometimes going beyond its boundaries) and banging the pen down hard, looking for a reaction from others.

Julie is often experimental – for example, attempting to draw without looking at her page. She has drawn for up to 40 minutes in one session and is reluctant to ‘finish’ her drawing. Her particular interest is drawing ‘scary’ creatures – skeletons, zombies, monsters, crocodiles, as well as re-living aspects of her favourite TV programme PJ Masks(Cat Boy is her favourite).

VALUABLE BENEFITS

There have been many unexpected and valuable benefits from the project. For example, a special feature of the sessions is that the child is asked to do one drawing only. Children are encouraged to accept their ‘mistakes’ or amend them, rather than begin a new drawing. Some children have found this frustrating initially, but have become used to this different and positive approach.

The sessions also develop children’s literacy skills, as they begin to realise the joy of drawing, turning to it more readily in their self-chosen play. It is also an ideal opportunity to model new language as part of natural conversations. When children draw in a small group, they also develop valuable social skills. Praise from their peers gives children a valuable confidence boost and a positive view of themselves.

WHAT NEXT?

As the series of sessions come to an end, the children will take their portfolio of drawings home. We would like to spend time with the parents sharing what their children have done so far and supporting them to carry on drawing sessions at home. We would also like to extend the number of children who benefit from the sessions by training other staff and volunteers in ‘drawing and talking’.

The looking glass theory of American sociologist Charles Cooley highlights the impact our social interactions have on our self-image. ‘When we encounter others,’ he writes, ‘we look to see how they are responding to us, similar to looking into a mirror to see how we look.’ Using PPF to support a child’s image, alongside their communication and literacy skills, has been one of our most successful and insightful projects.

We feel privileged to be able to support children’s positive sense of self, by reflecting back our interest, fascination and enjoyment of their company and communication.

Kelly Brooker is deputy head and Carrie Brown is an early years teacher at BEYA (kbrooker@beya.org.uk) (carriesb@gmail.com)

FURTHER INFORMATION

- Anning A and Ring K (2004) Making Sense of Children’s Drawings. Open University Press

- Gerhardt S (2004) Why Love Matters: How affection shapes a baby’s brain. Routledge

- O’Brien J (2011) The Production of Reality. Essays and Readings on Social Interaction. Sage

- Wright S (2007) ‘Young children’s meaning making through drawing and “telling”’. Australian Journal of Early Childhood, 32 (4), pp37-49