In the Community - At the museum

Christina MacRae

Monday, March 18, 2019

Museum visits with parents as ‘co-researchers’ brought about meaningful connections with two-year-olds, explain Dr Christina MacRae and members of the Martenscroft Nursery School and Children’s Centre research collective

Download the PDF of this article

Our research collective is a diverse and changing group consisting of parents, children, a school governor, early years practitioners, the early years co-ordinator from Manchester Museum and a researcher-in-residence from Manchester Metropolitan University. What connects us all is Martenscroft Nursery School and Children’s Centre, an early years setting located in Hulme, close to the city centre. And our recent question was: What can children and parents gain by making repeat visits to the same location?

As the nursery is located within walking distance to the Manchester Museum, this seemed an obvious destination. While nursery children had made various trips to the museum, it was a first for children from our two-year-old room.

We also wondered what would happen if we involved parents/carers and children in the documentation and collection of data, rather than leaving this process to either the researcher or the early years practitioners.

ON THE RECORD

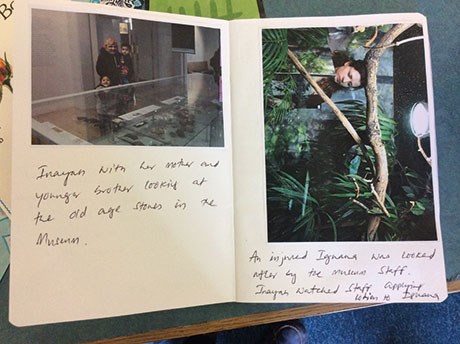

We made five weekly trips with the same group of children, and a parent with each child. Each parent had a small book in which they could make notes during or after the visits, and the other accompanying adults also took notes and photographs.

The research notebooks were distinctive in that they provided a way for children (as well as their parent) to capture the sessions on their terms: some with drawings, some who enlisted adults to draw or write things down, and some who took photos.

We discussed the question of ethics and data consent at the outset as some parents wanted to take and share museum photos on their mobile phones. So we needed to check that everybody was happy if, for example, a child requested a photo with another child, or if parents wanted to take group photos.

The notebooks became significant throughout the project, as families took them home after each visit and parents and children often stuck photos into them. Some parents wrote detailed observations, while others used the pictures as a means to recall and talk with their child about what had happened.

At home, notebooks were shared with other family members, extending the network of connections. One child insisted his family all sat down while he ‘read’ the book to them. In this way, the notebooks continued to evolve throughout the project in response to different home practices.

It was the photos and notebooks that we used in our ‘data-sharing’ workshop at Manchester Metropolitan’s Faculty of Education at the end of the project. The workshop gave us:

- thinking space to discuss our different perceptions of the trips

- space to look at the photographs taken by adults and by children

- time to pull together what seemed to be the most significant themes.

Our project was also documented in the classroom by means of a display, which included parents’ thoughts and observations, images and photocopied pages of the notebooks.

MAKING CONNECTIONS

An overarching theme that emerged was how the project had enabled participants to make connections with:

- each other

- things in the museum

- places and things on the way to the museum.

As well as connectedness, other key themes emerged when we discussed the data together.

Repetition

Making regular visits meant that the children were able to take the lead increasingly as they got to know how to find their favourite places and things. They started to anticipate what was coming next and would often recall and refer back to places, things and events from previous visits. In this way, their knowledge and meaning-making continued to develop throughout the project, often in new directions.

Sometimes this ‘connection-making’ was expressed non-verbally – for instance, one child developed a series of bodily movements in a specific part of a gallery, and directed sounds at a stuffed polar bear. This pattern of actions was repeated and developed over the visits.

Confidence

The repeated visits helped build children’s confidence. They looked forward to the trips as they knew where they were going, and gradually got closer to places or things that scared them.

For example, one of the first exhibits that you see on the grand stairway of the museum entrance is the stuffed tigon (a unique hybrid of lion and tiger). Initially, one child was very worried about going close to the glass, but by her final visit she approached the tigon singing, ‘You’re not scary, you’re not scary’, and she stroked the side of the glass saying, ‘Hello, Tigon.’

Group visits

Group visits enabled us to make connections with each other and tune in to each other’s different interests. They also offered children space to explore gradually. One parent expressed this as a ‘space to explore’ and say ‘go on son, I know where you are, just don’t go too far’.

We thought it was important to have the freedom just to be, with no hurry and no pressure. However, when we relaxed, we often found our interest was caught by some of the exhibits, which offered unexpected points of connection.

Some of the Egyptian exhibits had been excavated from land that now comes inside Sudan’s borders, and one parent was able to identify the region where his father’s village was on a map; another parent explained the story of Sudan’s independence.

One parent had experience of cooking over fires in earthenware pots similar to those in the museum and demonstrated to us how this was done. We all learned about, with and from each other.

The walk

The walk to the Museum was also special, as children began to anticipate landmarks on the way. For instance, one child created a particular running pattern each time we walked past a sloping ramped pavement. His step would quicken as we approached this spot, and it became a point of pride for him that other children began, over the weeks, to join him with his special ritual.

The walk to the Museum was also special, as children began to anticipate landmarks on the way. For instance, one child created a particular running pattern each time we walked past a sloping ramped pavement. His step would quicken as we approached this spot, and it became a point of pride for him that other children began, over the weeks, to join him with his special ritual.

On the way to the museum we passed a building site which also became a regular stopping point, where children peeked through spy holes checking on progress and even getting updates from the builders. Small things often matter most!

Photos

Photos in the notebooks and on mobile phones were ways of remembering visits and involving other family members and friends. Having the photos at home was important for non-verbal children as they could respond by pointing, making sounds, gesturing and turning pages.

Photos in the notebooks and on mobile phones were ways of remembering visits and involving other family members and friends. Having the photos at home was important for non-verbal children as they could respond by pointing, making sounds, gesturing and turning pages.

The notebooks became objects that moved between home, museum and nursery, and catalysts for memories, dialogues and connecting threads between the three sites.

Observations

One of the unexpected outcomes of the project was that parents’ thoughts and observations became a key part of the classroom display. While it is usual to have early years practitioners sharing their observations and documentation with parents, it is rare for parents to have the opportunity to share their observation and reflections of their children’s learning with practitioners.

This project highlighted the value of parents’ knowledge and combined it with that of children and early years practitioners. We are now hoping to extend this parent research and start more co-researched visits when the children have made the transition to the nursery class.

WHAT WE LEARNED TOGETHER

Having a notebook per family meant that the data had a life of its own as the project unfolded. The notebooks became points of connection – they provided threads of meaning that linked the small events of each visit to the lives of children at home and the nursery setting. But it was important that people used the books in their own ways – for some people, recording was less important, and for them the conversations during the visits and at our data-sharing event were more important.

It helps to have a central digital storage space before you start your project (we learnt this the hard way!).

At the beginning of the project all the participants need to discuss research ethics and decide whether people can take photos on their phones and on iPads, and how they will be used.

Organising regular trips takes time to plan and set in motion, and demands a time commitment from parents as well as practitioners. At the outset when we approached parents, it was important to make the time commitment clear; but we also discovered how valuable it was to learn from each other.

Being flexible enriches the project: for example, if one parent is unable to attend a visit, another family member can step in.