Early Years Pioneers - Margaret Carr

Linda Pound

Monday, February 6, 2017

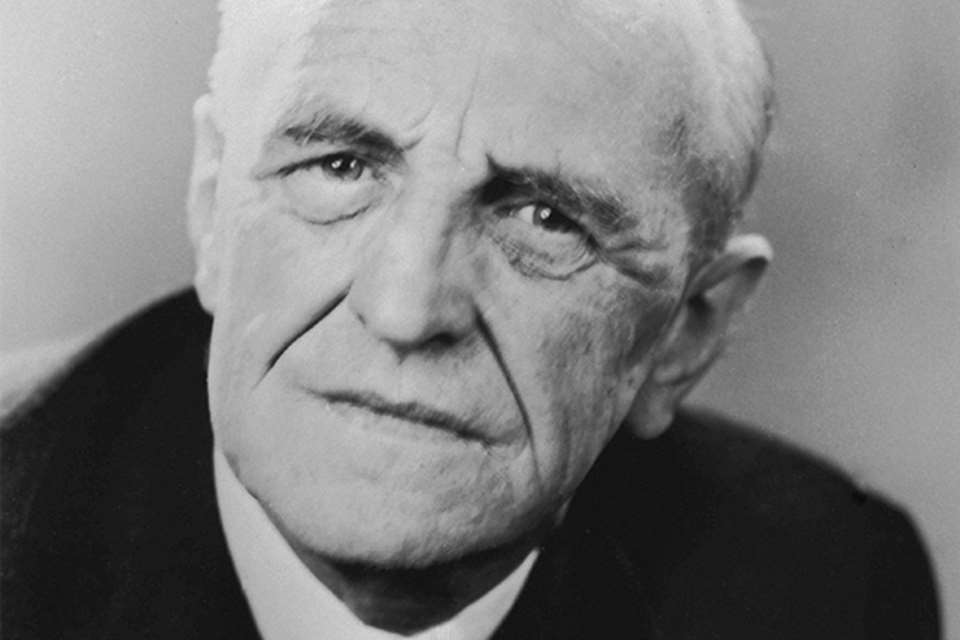

The woman behind New Zealand’s early years curriculum is still going strong. By Linda Pound

Margaret Carr, unlike many of the pioneer educationalists studied today, is alive, well and carrying on her ground-breaking work in the education of young children.

She is a professor of educational research at the University of Waikato in New Zealand, where she has been based for a number of years, and has been awarded the title of Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to early childhood. Her contribution is also recognised beyond her home country – having been endorsed by the OECD and invited to write a report for UNESCO.

Her research and writing cover a wide range of topics related to children’s learning dispositions and competencies.

Despite her many achievements, Professor Carr’s name is rarely singled out. In keeping with her interest in collaboration and community, she generally writes and researches with others. But she is the name behind New Zealand’s early years curriculum, known as Te Wha¯riki, as well as the associated approach to assessment, Learning Stories. It is undoubtedly these two areas which represent her greatest achievements.

Despite her many achievements, Professor Carr’s name is rarely singled out. In keeping with her interest in collaboration and community, she generally writes and researches with others. But she is the name behind New Zealand’s early years curriculum, known as Te Wha¯riki, as well as the associated approach to assessment, Learning Stories. It is undoubtedly these two areas which represent her greatest achievements.

TE WHA¯RIKI

Throughout the 1980s, as was the case in Britain, there was widespread concern in New Zealand about the disparate nature of early childhood provision. There were major differences in the amount of time children spent in pre-school institutions; the kinds of organisation they attended; their cultural context; and the focus of the curriculum.

In 1991, Professor Carr, together with her colleague Helen May, won a Government contract to develop curriculum guidelines that could be adopted by everyone. A draft version of Te Wha¯riki was published in 1993 and formally adopted in 1996.

Professor Carr argues that few curriculum documents have such an overt philosophical base. The underlying philosophy of Te Wha¯riki emphasises:

the socio-cultural nature of learning, in line with Vygotsky’s theories and building on the more recent theories of Urie Bronfenbrenner on the child within family and community

the motivational aspects of learning – such as perseverance, playfulness and exploration

children’s right to be heard, to be consulted and to express their views as laid down in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (articles 12 and 13).

Te Wha¯riki is a bilingual and bicultural curriculum framework. One of its many strengths is that from its inception, Ma¯ori educators were involved. Key to its development was the use of the Ma¯ori term, ‘mana’, which broadly means empowerment. Thus the first principle overarches all others, while the strands (with Ma¯ori names shown below) all involve empowerment – a concept which it is believed should permeate learning from birth. Mana incorporates the intention that learners are empowered in every possible way. The name Te Wha¯riki, also a Ma¯ori term, means woven mat – a term chosen to convey the interweaving of five strands (see box) and four broad principles:

Empowerment to learn and grow (whakamana): well-being(mana atua).

Holistic development: belonging (mana whenua).

Family and community: contribution (mana tangata).

Relationship with people, places and things: communication(mana reo) and exploration(mana aotûroa).

LEARNING STORIES

Since Te Wha¯riki offers a holistic view of learning, the process of assessment is complex. In 2001, Carr proposed what Anne Smith (2011) describes as ‘a holistic, transactional, formative assessment procedure entitled Learning Stories’. Its purpose is to document significant learning moments in children’s everyday experiences.

Learning Stories are focused on children’s disposition for learning, which have also been described as patterns of behaviour. Parents and children are invited to comment. Teachers add their voice, taking account of what has been said in order to identify next steps. Ms Smith refers to this focus on learning goals as highlighting competence – as opposed to performance goals which, she suggests, highlight failures.

Professor Carr and the New Zealand government have together produced a number of publications designed to support teachers in implementing Learning Stories. Examples are included and carefully annotated, showing what was happening, how each observation links to learning dispositions and how it will support learning and development overall.

RELEVANCE OF HER WORK

It is obvious from the many translations of her books – ranging from Cantonese to Danish – that Professor Carr’s work is widely regarded as highly relevant. In its respect for children, from birth, as competent learners, it has found a ready audience of early childhood practitioners eager for a framework which does not patronise them or the children they teach.

The fact that Te Wha¯riki strives to be relevant in individual, human, developmental, national and cultural terms, as well as educationally, contributes strongly to its relevance.

It is relevant because Professor Carr, together with Professor May and their Ma¯ori collaborators, Professor Sir Tamari Reedy and Lady Reedy, took steps to ensure that the curriculum they developed should be democratically developed, catering for the many cultures, indigenous and immigrant, living in New Zealand. Throughout the consultation period, discussions were held with teachers and parents from all sectors of early childhood provision.

Twenty years on, teachers remain positive because it is not a prescriptive document but respects educational practice and has a clear theoretical foundation. May and Carr are unapologetic about the theoretical basis of their document, arguing that it was never intended to be a set of activities to be followed blindly. Instead they worked to produce a framework to guide the practice of well-qualified, reflective early years practitioners – since these are essential to high-quality provision.

Learning Stories has also proved popular because it offers an approach to assessment which gives a voice to the relatively unheard views of young children and of those who work with them. Assessment can be used not merely to identify learning but to shape it. For early childhood educators whose view of children’s learning is often at odds with political views, Learning Stories offers an approach which chimes with their philosophy. Carr (2001) has identified some ways in which Learning Stories offer a better fit with current pedagogical views than checklists:

The purpose is to enhance learning in general, rather than to tick off a narrow set of competencies.

Outcomes reflect learning dispositions which will have relevance throughout life, rather than fragmented skills.

Validity is achieved through reflection and analysis rather than a questionable belief that observations can ever be objective.

Value to practitioners is achieved through discussion with children, parents, community and colleagues, rather than numerical totals.

CRITICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Despite its international success, there are criticisms of Te Wha¯riki. Some people have challenged its failure to live up to its declared focus on inclusion, suggesting that a single curriculum framework cannot cater for everyone and that resulting practice is not always inclusive.

There have been specific criticisms of Learning Stories citing issues such as subjectivity; judgements made on the basis of small amounts of evidence; and a neglect of vital knowledge and skills. It has been argued that neither approach offers sufficient accountability, but in 2012 a government taskforce published a report entitled Pathway to the Future, which set out a ten-year plan for increased accountability.

Some writers have been critical of the fact that the curriculum is not subject-based. They argue that this does not prepare children for statutory schooling and that some early childhood practitioners lack sufficient subject knowledge.

However, Professor Carr suggests that changes to the primary curriculum, giving a greater focus to key competencies, have brought it more into line with the lifelong approach adopted by Te Wha¯riki (Carr et al 2010).

TAKING A CHILD’S PERSPECTIVE

To take the child’s perspective in their learning stories, practitioners need to take account of the Te Wha¯riki strand, dispositions, and children’s questions to consider when assessing and planning learning

Well-being Trust and playfulness; courage and curiosity Can I trust you?

Exploration Persisting even when something is difficult and engaging with challenge Do you let me fly?

Communication Confidence in expressing a view or opinion Do you hear me?

Contribution Taking responsibility Is this place fair for me and my family?

(based on Ritchie 2005)

]]