Report warns 30 hours will mean less care for poorer families

Catherine Gaunt

Monday, March 7, 2016

If every week has a theme these days, last week could have been dubbed ‘free childcare stats’ week.

If every week has a theme these days, last week could have been dubbed ‘free childcare stats’ week.

First, a report from the National Audit Office (NAO) warned that poorer families could be pushed out by the Government’s drive to extend free childcare to 30 hours for three- and four-year-olds.

The report, ‘Entitlement to free early education and childcare’, also highlights providers’ concerns about the funding and warns that some settings may cut back on offering the more expensive two-year-old places so that they can expand provision for three- and four-year-olds.

This would jeopardise the Department for Education’s aim to improve educational outcomes for those who would benefit most from free childcare, the NAO says.

The report says take-up of two-year-old places is 58 per cent, based on figures from January 2015, and points out that the proportion of two-year-olds using free childcare varies widely across the country. In 2015, 30 local authorities had take-up rates lower than the national average, with Tower Hamlets the lowest at 26 per cent. However, the DfE has spent £7.4 million on promotion, including £5.4 million on the ‘Achieving for two-year-olds’ programme, and its new interim statistics show that take-up has risen to 72 per cent nationally (see pages 6 and 7).

Meanwhile, a separate DfE-commissioned parents’ survey shows that low-income families are less likely to use formal childcare.

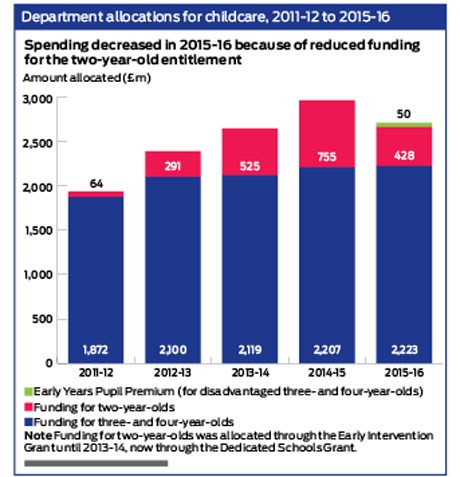

The NAO report raises concerns about the value for money of free childcare places for two-, three- and four-year-olds. It says that the Government is unable to track the effectiveness of the £2.7 billion invested in the funding of the free entitlement.

The quality of settings has risen, and the number of children reaching a good level of development at the end of the EYFS is now 66 per cent, according to EYFS Profile data, up from 52 per cent in 2013. But there is no way of linking data to the quality of the setting that children have attended; and the DfE intends to scrap the profile from next year.

The NAO also highlights early years providers’ concerns about the funding rates for the expansion to 30 hours. It notes that providers are ‘positive’ but concerned about whether the change will be affordable, with the new national average rates of £4.88 for three- and four-year-olds and £5.39 for two-year-olds.

It also points out that funding for free places has not risen since 2013, equivalent to a 4.5 per cent cut in real terms.

‘In many places the affordability of the current free entitlement depends on goodwill and additional payments by parents,’ the report says, adding that a review of costs by the DfE found that most providers rely to some extent on ‘cross-subsidisation between ages (as childcare is more costly for younger children). Providers report that they also rely on funds received for extra hours parents purchase. Additionally, they told us they rely on the goodwill of volunteers and on lower-paid workers who have a sense of vocation abut providing childcare.’

Nationally, local authorities kept back 10 per cent of early years funding centrally in 2014-15. If this were repeated, it would mean that new average funding rates would in fact be £4.85 for two-year-olds and £4.39 for three- and four-year-olds.

As well as the funding issues the report also points out that the DfE is unclear about what it wants to achieve through offering funded places.

It says that the success of the new entitlement will be difficult to measure: it gives higher priority to enabling parents to work than to improving children’s development, as evidence shows that full-time early years education does not have an extra impact on children’s outcomes beyond what part-time early years education achieves.

The new entitlement is likely to replace private funding for many parents who already pay for more than 15 hours’ childcare.

‘Beyond subsidising these parents’ costs, the department will need to set out what – if anything – it wants to achieve,’ the report says. ‘The department has not yet stated, for instance, to what extent it expects parents to work more hours as a result of the policy. Given the size of the investment, it will need to find measurable ways to track impact.’

INCOME IMBALANCE

Other DfE research, also published last week, shows that use of formal childcare is lower among poorer families.

The ‘Childcare and Early Years Survey of Parents in England 2014-15’ found that just 49 per cent of children in deprived areas receive formal childcare, compared with 65 per cent of families in better-off areas.

Take-up of the funded places among three- and four-year-olds is 80 per cent for families earning less than £10,000 a year, but rises to 94 per cent among those earning £45,000 or more.

Imelda Redmond, chief executive of 4Children, commented on ‘a worrying lack of progress in the use of formal childcare in more deprived areas. High-quality childcare is vital for children in their early years and can have a significant impact on their future prospects.’ She said the difference in take-up between children in the least deprived and most deprived areas was ‘a social mobility issue’.

She added, ‘There has been no improvement in these rates since 2013 – if we are to close the attainment gap that is already obvious when children start school, increasing quality childcare usage in deprived areas must be a priority. Lower-income families are already less likely to receive government-funded 15 hours of early education – we need renewed efforts to ensure the new 30 hours’ entitlement focuses on improving take-up of quality childcare in more deprived parts of the country.’

COMMENT: DR EVA LLOYD

COMMENT: DR EVA LLOYD

‘In its latest report, NAO in its usual transparent and pragmatic fashion not only states significant progress since 2010 in delivering the entitlement to free early education and childcare, but also lucidly identifies two factors underlying the policy’s striking failure to provide full value for money.

‘One is the DfE’s confusion about what it wants to achieve with the entitlement to free early education and childcare, something already highlighted in research by IFS and others, and the second is a crucial lack of information on the policy’s impact on children, families and the labour market, since measures to evaluate its effectiveness are lacking as yet.

‘The report highlights the potentially corrosive effect of continuing and often inexplicable variations both in local authority funding rates for the entitlement and in the amount they retain from the DfE allocation, which is 10 per cent on average. Such variations occur even between statistically similar authorities. The NAO does recognise, though, the role played in this by the historically uneven allocation from the DfE, as well as noting that local authorities spent £233 million more on providing the free entitlement in 2013/14 – the last year for which data was available – than they were allocated by the DfE.

‘In its analysis of the relationship between both local authorities’ and providers’ costs and available funding, the report comes down firmly on the side of the early years sector and their argument that the entitlement is underfunded. It quantifies the impact of the 2013/14 funding freeze on providers; this amounted to a cut in real terms of 4.5 per cent. But its most stinging critique is reserved for the DfE’s forward plans for the national funding rate from 2017. Helpfully doing the sums for us, the NAO team works out that the average national rate for three- and four-year-olds will go down by 49p per hour, and for two-year-olds by 54p per hour, if national LA retention rates are kept at 10 per cent. Presumably this loss would be amplified by the pension commitments providers are also expected to enter into, therefore we may well conclude that this rate will put provider sustainability at serious risk in many parts of the country.

‘However, the NAO team’s most explicit health warning is reserved for the risks inherent in the new 30 hours entitlement on the availability of places for disadvantaged two-year-olds. This entitlement’s potential to act as a perverse incentive to providers to favour the provision of three- and four-year-old places may give rise to the unintended consequence of the DfE failing to deliver on its commitment to some of England’s most disadvantaged children. The NAO team urges the DfE to study carefully the consequences in the eight Early Implementer areas before the national roll-out.

‘This report comes at the right time and provides valuable evidence in support of local government and early years sector arguments that children and families deserve a more coherent, fair and stable early childhood service system than the present one and that there are alternative routes to achieving this.’

Dr Eva Lloyd is professor of early childhood, Cass School of Education and Communities, at the University of East London